Current News

/ArcaMax

In dispute over electronic monitoring releases, are Las Vegas police flouting court orders?

LAS VEGAS — Judges in multiple recent cases have ordered the release of defendants on electronic monitoring, a program run by the Metropolitan Police Department, only to have police refuse to follow the decisions.

The conflict is now before the Nevada Supreme Court, with pending challenges filed by both Metro and the Clark County public ...Read more

Beale AFB tanker plane lands with damage, linked to deadly KC-135 crash in Iraq

A KC-135 Stratotanker that made an emergency landing in Israel after a mission in Iraq — where another tanker crashed, killing six U.S. service members — appeared to be assigned to Beale Air Force Base near Marysville, California.

U.S. Central Command said the KC-135 Stratotanker went down Thursday in western Iraq while flying in friendly ...Read more

Trump administration orders restart of oil drilling along California coast amid Iran war

President Donald Trump is asserting executive authority to demand the controversial resumption of offshore oil drilling along California’s coastline as gas prices soar amid the ongoing war with Iran.

On Friday, Trump signed an executive order giving the Department of Energy the ability to use a Cold War-era law known as the Defense Production...Read more

This Southern Nevada city is the state's only Lake Mead user that doesn't send water back

LAS VEGAS — Boulder City proudly proclaims itself as the home of Hoover Dam.

But for decades, despite its proximity to Lake Mead, it has only taken water from the reservoir without giving any back, lagging behind other Southern Nevada cities that now recycle nearly every drop used indoors.

That could change soon, officials say.

“We’ve ...Read more

Trump officials direct Sable to resume California oil operations

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration on Friday took action to clear the way for oil production off the California coast in a bid to ease the global fuel pressures created by the war with Iran.

The announcement by Energy Secretary Chris Wright follows an executive order signed by President Donald Trump on Friday and directs Sable Offshore ...Read more

News briefs

Armed Services members in the dark on details of war costs

WASHINGTON — The House and Senate Armed Services panels have yet to be briefed on the costs of the Iran war, members and aides said Thursday.

This week, Pentagon officials gave the Senate Defense Appropriations Subcommittee an estimate of $11.3 billion for the war’s first week, a ...Read more

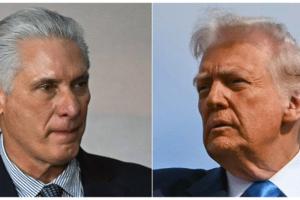

Cuba, reeling from oil crisis, acknowledges talks with Trump

MEXICO CITY — Cuba, reeling from an oil shortage, has begun direct talks with the United States in an effort to solve “bilateral differences” between the two countries, Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel said Friday.

The comments, broadcast nationwide in Cuba, are the first confirmation of negotiations between the Trump administration ...Read more

Travis Kalanick debuts plan for 'gainfully employed robots'

Uber Technologies Inc. co-founder Travis Kalanick has launched a new venture that will focus on creating “gainfully employed robots” for the food, mining and transport industries.

Kalanick is remaking his real estate company, City Storage Systems, which owns ghost-kitchen operator CloudKitchens, and renaming it Atoms, according to a ...Read more

Massachusetts Gov. Healey, AG Campbell launch new online portal for residents to report ICE misconduct

BOSTON — Gov. Maura Healey and Attorney General Andrea Campbell have launched a new online portal that will allow residents to report misconduct by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents conducting operations in the state.

“Please use this form to report potentially unlawful activity or misconduct by ICE and other federal agents ...Read more

Epstein orbited Peter Thiel for years over money, connections and advice

A few weeks after allegations surfaced in the global media that Jeffrey Epstein forced a teenager to have sexual relations with Prince Andrew, the financier contacted tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel to say he had two finance ministers and “a bunch of bankers” for him to meet in New York.

“Does my bad press give you pause,” Epstein added ...Read more

Michigan Sen. Slotkin seeks to 'bring temperature down' in wake of Temple Israel attack

WEST BLOOMFIELD TOWNSHIP, Mich. — U.S. Sen. Elissa Slotkin was in Michigan on Friday, the day after a Metro Detroit temple was attacked, working with Jewish and Lebanese American community leaders to find a way forward.

“Leaders have the responsibility to bring the temperature down, to remain calm and to lead with purpose in mind," Slotkin ...Read more

Trump replaces Kennedy Center President Richard Grenell, marking the end of a controversial tenure

President Donald Trump announced on social media Friday that Richard Grenell, the former ambassador to Germany who Trump appointed as president of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts more than a year ago, is stepping down. Grenell will be replaced by Matt Floca, the vice president of facilities operations at the center.

Change ...Read more

US hits military targets on Iran's Kharg Island as war escalates

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump said the United States had bombed military targets on a critical Iranian outpost in the Persian Gulf and threatened additional strikes targeting oil infrastructure if Tehran continued to block energy flows, in the latest escalation of the two-week conflict that has upended the region.

Trump said the U.S. ...Read more

'Not the first time': Cuba compares Trump talks to Obama era

Cuban leader Miguel Díaz-Canel confirmed the government’s talks with the United States on Friday — and tried to draw an unlikely parallel between Donald Trump and Barack Obama.

“It is not the first time that Cuba has entered into a conversation of this type,” Díaz-Canel said in a rare public address. “I believe that the most recent ...Read more

Synagogue attacker died of self-inflicted gunshot and had fireworks in truck, FBI says

WEST BLOOMFIELD TOWNSHIP, Mich.— A Dearborn Heights man who attacked Temple Israel in West Bloomfield on Thursday and engaged in a gunfight with security officers died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, the FBI said on Friday.

Ayman Ghazali, 41, of Dearborn Heights allegedly slammed his Ford F-150 through the front doors of Temple Israel on ...Read more

Idaho Republicans want to remove 'likely unconstitutional' word in abortion law

BOISE, Idaho — Idaho lawmakers are trying to strengthen the state’s “abortion trafficking” law after a legal challenge.

The law bans people from helping minors get an abortion in a state where it’s legal without a parent’s consent.

Gov. Brad Little signed the law in 2023, the first legislative session after the U.S. Supreme Court ...Read more

6 US airmen die in crash; 2,500 Marines being sent to the Middle East

WASHINGTON — Six American airmen deployed to operations against Iran were killed after their refueling aircraft crashed in western Iraq, U.S. Central Command said Friday, bringing the U.S. death toll in the war to 13, as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth ordered a deployment of Marines to the region ahead of the heaviest day of strikes yet.

The...Read more

Old Dominion shooter bought gun used in attack on ROTC classroom from Virginia man, ATF says

NORFOLK, Va. — A Virginia man was charged in federal court Friday with selling Mohamed Jalloh the gun that was used in the attack at Old Dominion University.

Jalloh bought it from the man during the last week for $100, according to an affidavit filed Friday by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

Jalloh was still on ...Read more

Philly sues Glock, saying manufacturer contributed to gun violence crisis

PHILADELPHIA — Philadelphia has filed a lawsuit against firearms manufacturer Glock Inc. alleging that the company has contributed to gun violence in the city through deceptive marketing practices that target young people.

Announced Friday, the lawsuit claims Glock promotes the use of “switches,” small devices also known as auto sears ...Read more

NYC no longer covering legal bills for former mayoral aide Tim Pearson in sex harassment, retaliation suits

NEW YORK — Taxpayers will no longer foot the bill for the legal representation of former Mayor Eric Adams' aide Tim Pearson in lawsuits accusing him of sexual harassment and retaliation, Corporation Counsel Steve Banks said Friday.

“Based on my review of new evidence since the original decisions were made, I have determined that he is not ...Read more

Popular Stories

- 6 US airmen die in crash; Hegseth says Iran's leader is 'likely disfigured'

- FBI busts Massachusetts convenience store clerks for 'staged armed robberies' to apply for immigration benefits

- Victoria Gotti doesn't want son Carmine's kidney if he goes to jail

- How sewage treatment plants could handle food waste, sparing landfills and the climate

- Afghanistan says Pakistan strike on Kabul leaves 4 dead