France forced Haiti to pay for independence. 200 years later, should there be restitution?

Published in News & Features

Two centuries ago this month, France pulled off one of history’s greatest armed extortions: After the first three leaders of a newly freed Haiti refused to cave in to hefty French demands to compensate its former slave-holders in exchange for recognition of its freedom, the European power finally succeeded in getting its demands met.

With a fleet of offshore French ships aiming their guns at Haiti, President Jean-Pierre Boyer, who would reunite a divided Haiti after the tragic and sudden deaths of King Henry Christophe in the north and President Alexandre Pétion in the south, bowed to French pressure and agreed to pay 150 million gold francs.

On April 17, 1825, France’s King Charles X officially imposed the ransom for the country’s independence. It stipulated Haiti would pay the massive sum to “compensate former colonists” who lost their property, including slaves, in exchange for recognition of its independence.

The story of Haiti’s debt has long been dismissed in France, whose wealth was partly built on the backs of enslaved Africans and their descendants who were brought to work the fields of what was then its richest — and harshest — slave colony, Saint Domingue. Instead of being described as a ransom payment, the debt and the French king’s gunboat extortion were framed as emancipating the slaves who, after defeating the world’s most powerful army, declared the new nation of Haiti on Jan. 1, 1804.

Last week, after decades of distorted narratives, French President Emmanuel Macron said he would announce “several memory initiatives” to “keep alive the memory of slavery throughout the national territory, as in Haiti.” He chose as the date to do this April 17, the 200th anniversary of France’s recognition of Haiti’s independence and the date of King Charles’ imposition of the debt.

Macron’s announcement comes as demand has grown for greater recognition of what France’s “independence debt” did to Haiti’s development. It also comes amid a debate about reparations, and whether there should be financial restitution for the debt.

“What is most important for us is not the symbolic recognition. What’s most fundamental is restitution and reparations,” said Bildadson Cadelus, a member of Haiti’s National Committee on Restitution and Reparations.

Pierre Buteau, a Haiti historian, said to answer whether there should be financial restitution for the debt “we have to know how it was constructed” and it has to be based on solid research. He dismisses the notion that Haiti’s historical instability is solely based on that debt, and warns that repayment, despite what some critics say, is not “the thing that is going to allow Haiti to get out of its current crisis.”

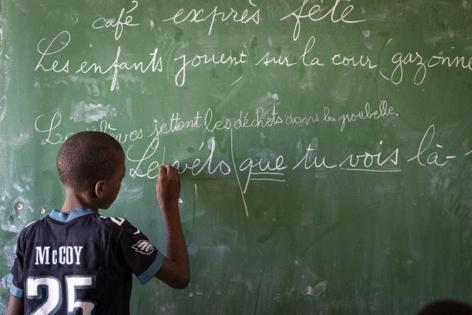

Like many who have closely followed the issue, Prof. Marlene Daut has watched France and its leaders go from spin and denial to willingness to have a conversation. Still missing, she says, is an apology and the acknowledgment of the need for justice. After the imposition of the debt, Haiti went from a nation building a national education and health system under Christophe to enforcing a rural code for laborers under Boyer to pay the debt.

France “created a debt where there was none,” said Daut, who authored the recently published book, “The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe,” which takes a deep look at the debt and argues that it put Haiti on the road from prosperity to poverty. “That was actually a remarkable thing to turn a country that was a producing country ... into a debtor nation. Who knows where the progress that Haiti was making on its own linear path would have taken it? We don’t know where, but we know when the path was predetermined for them.”

Daut, who teaches at Yale University and is an expert on the Haitian Revolution, said while she welcomes the new momentum around the issue of the debt, she is not “expecting any miracles on April 17,” but is curious to see what how Macron treats the matter.

For years, the French president has offered no comment when asked about the debt and tiptoed around the subject of the implications of slavery. In 2023, as he delivered a speech on the 175th anniversary of France’s abolition of slavery by paying tribute to Toussaint Louverture, a leader of the Haitian Revolution, Macron did not mention that Louverture had been tricked by France and then taken there, where he died in prison. Nor did he mention France’s ransom demand from Haiti.

Colonial oppressor

Still, France’s role as a colonial oppressor and its fraught history with Haiti is increasingly being recognized in Paris, where there’s now a nuanced conversation around the issue.

“Memory feels innocuous and therefore safe. You say, ‘Oh, we need to remember. We need to commemorate. But then you don’t have to do anything. It’s as if remembering is enough. But in this situation, there are actual people who are harmed, generationally so, and they deserve re-compensation,” Daut said. “Even if France’s actions were legal in the era, were they morally correct? Does it make them civilly responsible for the ills that befell Haiti? I mean, there’s plenty of lawyers who think so.

“It is true that they used to deny it, or really just kind of try to say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter.’ So now we’ve gotten to talking about it, we need to get them doing something about it,” Daut said.

Haiti’s leaders have recently raised the matter of the debt. Former foreign minister Dominique Dupuy brought it up at both a Conference on the African Diaspora Conference in Brazil and a July 14 Bastille Day celebration at the French Embassy in Port-au-Prince. The two most recent heads of the Transitional Presidential Council, Leslie Voltaire and Edgar Leblanc Fils, later followed suit. Voltaire raised it with Macron earlier this year during a visit to Paris and Leblanc made the case during his address last fall at the United Nations General Assembly.

“We demand recognition of the moral and historic debt and implementation of justice,” Leblanc said as he underscored how the debt had hobbled Haiti’s development.

The most high-profile moment, however, came in 2003 ahead of Haiti’s bicentennial. Former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, shortly before he was forced from power, demanded France repay the money and presented a price tag in modern terms: more than $21 billion.

The debt was initially 150 million francs, or 10 times the amount charged the U.S. for the sale of the Louisiana territory in 1803 in order to raise money to fight Haiti’s revolutionaries. The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States.

Haiti, which declared its independence on Jan. 1, 1804, and defeated Napoleon’s army soon after, didn’t have the money to pay the debt, Daut points out in her book. The French government required the country to borrow 30 million francs from French banks to make the first two payments, and Haiti soon defaulted.

In 1838, another French expedition of 12 warships was deployed to Haiti, and its government was forced into a new treaty. The total debt was reduced to 90 million francs. Haiti’s government was once again ordered to take out high-interest loans to pay the balance.

‘A state made to fail’

When the U.S. occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934, it had control over the country’s finances — and continued to enforce payment of the debt, which Haiti did not finish paying off until 1947.

“When people tell me, Haiti is a failed state, I say ‘No, Haiti is a state that was made to fail.’ There’s a huge difference,” Daut said.

Like many historians, Daut says she has been thinking a lot about what restorative justice should look like. The conversation around restitution in the Caribbean is not unique to Haiti.

Sir Hillary Beckles, a professor at the University of the West Indies who years ago raised the issue around restitution from England, Spain, Portugal and France to its former colonies in the region, has argued for assistance with development As chairman of the Caricom Reparations Commission, Beckles has introduced a 10-point plan that calls not just for a formal apology by the governments of former slave-holding European nations, but for investments to help address the public health crisis in the Caribbean. He argues, for example, that the Caribbean population’s high incidence of chronic disease in the form of diabetes and hypertension is linked to the diets of slaves, introduced by the colonizers, and continues to have lingering effects today.

“I’ve been involved in conversations with people who talk about restorative justice, and yes, there can be and usually there is some form of monetary compensation, but there are also other ways to provide restorative justice,” Daut said.

“There’s so many things that could go into this,” she added. “It’s building infrastructure, asking people and figuring out what people need and bringing it to them. Not from a standpoint of aid, but of restorative justice. Because that’s different.”

_____

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments