I study local government and Hurricane Helene forced me from my home − here’s how rural towns and counties in North Carolina and beyond cooperate to rebuild

Published in News & Features

Last year was a record year for disasters in the United States. A new report from the British charity International Institute for Environment and Development finds that 90 disasters were declared nationwide in 2024, from wildfires in California to Hurricane Helene in North Carolina.

The average number of annual disasters in the U.S. is about 55.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency provides funding and recovery assistance to states after disasters. President Donald Trump criticized the agency in January 2025 when he visited hurricane-stricken western North Carolina. Though 41% of Americans lived in an area affected by disaster in 2024, according to the institute’s report, the Trump administration is reportedly working to abolish or dramatically diminish FEMA’s operations.

“FEMA has been a very big disappointment. They cost a tremendous amount of money. It’s very bureaucratic, and it’s very slow,” Trump declared, saying he thought states were better positioned to “take care of problems” after a disaster.

“A governor can handle something very quickly,” he said.

Trump’s remarks have prompted a heated response, including proposals to fundamentally overhaul – but not abolish – federal disaster recovery.

But I believe the current discussion about FEMA handling U.S. disasters puts the emphasis in the wrong place.

As a scholar who researches how small and rural local governments cooperate, I believe this public debate demonstrates that many people fundamentally misunderstand how disaster recovery actually works, especially in rural areas, where locally directed efforts are particularly key to that recovery.

I know this from personal experience, too: I am a resident of Watauga County, in western North Carolina, and I evacuated during Hurricane Helene after landslides severely impaired the roads around my home.

Here, in short, is what happens after a disaster.

Federal legislation from 1988 called the Stafford Act gives governors the power to declare disasters. If the president agrees and also declares the region a disaster, that puts federal programs and activities in motion.

Yet local officials are generally involved from the very start of this process. Governors usually seek input from state and local emergency managers and other municipal officials before making a disaster declaration, and it is local officials who begin the disaster response.

That’s because small and rural local governments actually have the most local knowledge to lead recovery efforts in their area after a disaster.

Local officials determine conditions on the ground, coordinate search and rescue, and help bring utilities and other infrastructure back online. They have relationships with community members that can inform decision-making. For example, a county senior center will know which residents receive Meals on Wheels and might need a wellness check after disaster.

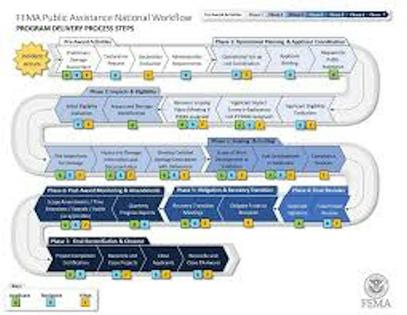

However, small towns cannot do all this alone. They need FEMA’s money and resources, and that can present a problem. The process of applying and complying with the requirements of the grants is incredibly complex and burdensome. According to FEMA’s website, there are eight phases in the disaster aid process, composed of 28 steps that range from “preliminary damage assesment” to “recovery scoping video” to “compliance reviews” and “reconciliation.” Getting through these eight phases takes years.

Larger cities and counties frequently have dedicated staff that apply for disaster aid and ensure compliance with regulations. But smaller governments can struggle to apply for and administer state or federal grants on their own – especially after a disaster, when demands are so high.

That’s where regional intergovernmental organizations come in. Every region has its own name for these entities. They’re often called councils of government, regional planning commissions or area development districts. My colleagues and I call them RIGOs, for their initials.

No matter the name, RIGOs are collaborative bodies that allow local governments to cooperate for services and programs they might not otherwise be able to afford. Bringing together local elected officials from usually about three to five counties, RIGOs help local officials cooperate to address the shared needs of everyone in their area. They do this in normal times; they also do this when disasters strike.

RIGOs operate throughout most of the U.S., in big cities and rural areas, in turbulent times and in calm. They serve different needs in different regions, but in all cases, RIGOs bring together local elected officials to solve common problems.

One example of this in western North Carolina is the Digital Seniors project, launched during COVID-19. Here, the local RIGO is called the Southwestern Commission. In 2021, the RIGO area agency on aging coordinated with the Fontana Regional Library to help dozens of elders who had never been connected to the internet get online during the pandemic. The Southwestern Commission used its relationships with the local senior centers to identify people who needed the service, and the library had access to hot spots and laptops through a grant from the state of North Carolina.

In rural areas, RIGOs work alongside regional business and nonprofits to allow local governments to offer regular services and programs they might not otherwise be able to afford, such as public transportation, senior citizen services or economic development.

Part of that work is helping member governments navigate the maze of federal and state funding opportunities for the projects they hope to get done, often by employing a specialized grant administrator. Each small local government may not have enough work or revenue to justify such a staff member, but many together have the workload and funding to hire someone specially trained to abide by the rules of funding from states and the federal government.

This system helps small local governments receive their fair share in federal grant money and report back on how the money was spent.

Disasters rarely respect borders. That’s why governments generally work together to distribute grant money for rebuilding communities.

In the summer of 2022, eastern Kentucky faced deadly flooding after receiving about 15 inches of rain over four days – 600% above normal. The North Fork of the Kentucky River crested at approximately 21 feet, killing over two dozen people and damaging 9,000 homes and more than 100 businesses.

The Kentucky River Area Development District, a RIGO representing eight counties, played a key role in the area’s recovery. It secured millions in FEMA aid and maintained critical services, including expanded food delivery and transportation for elderly residents.

Similarly, after disastrous flooding hit Vermont in 2023 and 2024, another RIGO, the Central Vermont Regional Planning Commission, jumped into action. It quickly provided emergency communication to the 23 small villages and towns in its region and has since supported local governments applying for grants and reimbursements.

Today, it continues to assist in Vermont’s disaster planning and flood mitigation. This is also part of the recovery process.

Rebuilding after a disaster is a long, arduous process. It begins after national journalists and politicians have left the area and continues for years. That would be true no matter how Trump restructures emergency aid: The damage is massive, and so is the repair.

For example, here’s how western North Carolina looks six months after Helene: Most businesses have reopened, most folks have running water again, and people can drive in and out of the area.

But many roads are still full of broken pavement. Mud from landslides presses up against the sides of the highway, and condemned housing teeters on the edge of ravaged creek beds.

It is, in other words, too soon to see the full impact of local government efforts to rebuild my region. But RIGOs across the region are hiring additional temporary staff to help local governments get federal money and comply with complex guidelines. Their support ensures that decisions affecting North Carolinians are voted on by the city and county leaders they elected – not decreed by governors or handed down from Washington, D.C.

Locally led rebuilding is slow and difficult work, yes. But it is, in my opinion, the most community-responsive way to deal with disaster.

Jaylen Peacox, a graduate student in public administration at North Carolina State University, contributed to this story.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jay Rickabaugh, North Carolina State University

Read more:

If FEMA didn’t exist, could states handle the disaster response on their own?

Beyond bottled water and sandwiches: What FEMA is doing to get hurricane victims back into their homes

New flood maps show US damage rising 26% in next 30 years due to climate change alone, and the inequity is stark

Jay Rickabaugh receives grant funding from the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Comments