California high-speed rail may lose $4 billion. Should it continue?

Published in News & Features

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — More than a month after the Trump administration moved to rescind $4 billion in expected funding, the future of California’s high-speed rail project remains uncertain.

The money hasn’t been reallocated yet, and California is challenging the decision. But the attempted funding cut has reignited long-standing doubts about whether the nation’s most ambitious rail project can still deliver on its promise.

The project has always carried outsized ambitions. When voters approved a $10 billion bond for the project in 2008, the plan was to connect Los Angeles and San Francisco in under 3 hours via fully electric-powered high-speed rail by 2020, at a cost of $33 billion. Then, in a second phase, the system would be expanded up to Sacramento and down to San Diego.

Since then, it’s been battered by delays, lawsuits and escalating costs to potentially over $100 billion. Its first operable segment in the Central Valley— a 172-mile stretch between Merced and Bakersfield slated to open in 2033 — is far from the original vision and the $14 billion needed to close the funding gap by June 2026 remains elusive.

President Donald Trump has lambasted the project as a “boondoggle” and a “high speed train to nowhere.”

“We’re not going to fund that….it’s out of control,” Trump said at a news conference. “It doesn’t go where it’s supposed to.”

A 310-page federal oversight report in June described it as a “Sisyphean endeavor” — a characterization Ian Choudri, CEO of the High-Speed Rail Authority, called misleading. Critics, particularly from libertarian and fiscally conservative think tanks, have long derided the plan as overly ambitious and unnecessary. Even former state officials involved in the project have publicly voiced regrets and frustrations.

Yet the project still has powerful defenders — Gov. Gavin Newsom, major labor and environmental groups, and many transit experts — who argue that despite early mistakes, the state can’t afford to walk away.

California has sued, challenging Trump. “It’s yet another political stunt to punish California,” Newsom said in a news release.

As of August 2025, over 463 miles of track have cleared environmental review and are construction ready, and roughly 119 miles are currently under construction between Shafter and Madera, according to authority spokesman Kyle Simerly.

Supporters say the rail line offers a climate solution, a transportation backbone for a growing state and a long-overdue shift in American travel habits. It has also generated more than 15,500 construction jobs — most filled by Central Valley residents, according to Simerly.

Yet with the project scaled down and skepticism rising over ridership and returns on investment, the federal government’s threat to pull $4 billion in funding raises unavoidable questions about whether the project’s demand still justifies its cost.

The costs of high-speed rail

High-speed rail is expensive — and everything is getting more expensive. Andy Kunz, president of the U.S. High Speed Rail Association, said, “Everything is just making this upwards creep — labor, insurance, cement, steel.”

The project faces geometric constraints as its gradients have to be much less steep than highways, Lou Thompson, former rail authority peer review group chair, said. This limits their route flexibility, and the plan’s linear nature means it intersects with many jurisdictions.

Environmental review laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the California Environmental Quality Act, add years to the timeline and open the door to litigation. Though well-intentioned, “they’re used by not-in-my-backyard people to stop projects,” said Baruch Feigenbaum, senior managing director of transportation policy at the libertarian think tank Reason Foundation.

Some mistakes were self-inflicted. Pressure to spend federal stimulus funds led the authority to begin construction before it had final designs or full clearances, resulting in costly overruns, Thompson said.

Others argue the state missed a major opportunity: routing the line along the I-5 corridor could have reduced costs by using existing federal right-of-way and bypassing dense urban areas. But that idea was set aside for political reasons — to secure support from Central Valley voters and lawmakers, said Ethan Elkind, an attorney and environmental law expert at UC Berkeley.

The project has also been plagued by its heavy reliance on outside consultants — a symptom of the nation’s underdeveloped in-house infrastructure delivery capacity compared to other countries.

Another driver of cost escalation is pressure from local stakeholders, who often raise concerns or push for additional amenities, said Eric Goldwyn, a transportation researcher at New York University. In Shafter, the rail authority secured $202 million in federal funding for grade crossings to improve traffic separation — some of which were parallel builds not directly part of the rail project. In Kern County, a reroute to shift the tracks farther from the César Chávez National Monument added roughly $1 billion, he said.

“These projects end up being about much more than just building rail,” Goldwyn said. “Every town is going to get significant capital improvements” — roads, sewers, utilities and new stations — that wouldn’t have been funded otherwise.

Railroad, highway or airport?

The authority’s 2019 Equivalent Capacity Analysis Report estimated that upgrading highways and airports to match high-speed rail’s planned capacity would cost $122 billion to $199 billion.

The comparison has limits, several experts noted: It weighs two fundamentally different kinds of builds. Though high-speed rail requires constructing entirely new corridors, they’re often running through rural land, but highway and airport expansions typically retrofit complex urban spaces — a far messier, costlier task. Airports in San Francisco and Los Angeles are hemmed in by urban development, and widening highways like Highway 99 would carve through cities and require expensive land acquisitions, Elkind said.

Other alternatives would include upgrading the existing Amtrak line and scaling luxury buses between San Francisco and Los Angeles. But the key comparison is air travel, Feigenbaum from the Reason Foundation believes; driving serves a more flexible range of trips and intercity buses appeal to different demographics as high-speed rail targets business travelers willing to pay premium fares.

Backers emphasize the environmental case: shifting travelers from cars and planes cuts emissions and highway congestion. The rail project also encourages compact, infill development, preserving farmland and open space. Elkind compares it to electric vehicles: “high emissions to build, but major long-term savings.”

Feigenbaum argues that while high-speed rail is energy efficient, the emissions payback timeline might be longer than expected. A 2010 life-cycle assessment by UC Berkeley researchers found that the project might take decades to offset the greenhouse gases generated by its energy-intensive construction — and that payoff hinges largely on how many people actually ride it.

The ridership question

In their 2024 Business Plan, the High-Speed Rail Authority lowered its ridership forecast for the Merced-to-Bakersfield segment from 38.6 million (projected in 2020) to 28.39 million, citing slower-than-expected population and economic growth in the region.

Forecasting ridership is notoriously tricky. “We’re trying to forecast demand for something that doesn’t exist and has never existed in California,” Thompson said.

Demand depends on myriad factors such as population density, station-area development, pricing and travel speed. Starting in the Central Valley — a region with fewer jobs and lower density — presents challenges, Elkind said. Without strong infill incentives and regional land-use coordination, ridership will suffer.

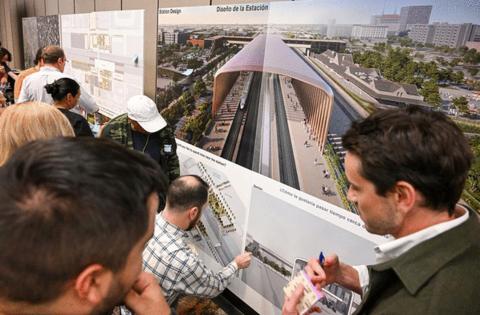

Elkind warned that fragmented land use planning could undermine high-speed rail. It’s still far cheaper to permit suburban sprawl on farmland than to build dense housing near stations — especially when nearby jurisdictions aren’t aligned. And recently, the Authority announced in May it plans to downsize its original plan for its large downtown Fresno station, in anticipation of federal funding cuts.

If Merced to Bakersfield is the only segment built in the near term, it’s “imperative” to maximize its value, said Sebastian Petty, a senior transportation policy advisor at the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association. That means building dense, walkable neighborhoods around stations — or risk low ridership and unsustainable operations.

Closing the gap

The loss of $4 billion in federal funding leaves California scrambling to fill a deep financial gap of $14 billion to even finish the Central Valley corridor.

Thompson, the former peer review group chair, stressed the urgency of retrieving the federal funding or finding new state funding. Without that, even the Merced to Bakersfield line may be a pipe dream. “If we in California want to do this, we’re going to have to figure out how to pay for it,” he added.

So far, the project has been funded largely through California’s cap-and-trade program, which auctions a limited number of emission permits to companies. Proceeds from this have raised about $6.4 billion for the project from 2012 to 2023. Newsom has proposed expanding this program to guarantee a minimum of $1 billion of state funds per year through 2045. The Authority has turned to private investors for financial support and feedback and began fielding expressions of interest in June.

“Being able to point to an ongoing stream of committed state funding is going to be really critical,” said Petty.

And to address delays from the regulatory process, SB 445, a bill moving through the Assembly from Sen. Scott Wiener, would set strict timelines and coordination rules for outside agencies to streamline permitting and keep high-speed rail construction on track.

But Reason Foundation’s Feigenbaum is more pessimistic. He believes private investment won’t come forth until there’s proven demand.

Feigenbaum argues the project continues largely for symbolic reasons and because of political pressure. He believes high-speed rail might still succeed in the U.S., but only in denser, shorter corridors like the Northeast. If California were to abandon its current effort, he said, the right-of-way could be repurposed — for housing, linear parks, or trails.

But Kunz, the president of the US High Speed Rail Association, points to the 400 miles of track that have already cleared environmental review — an “enormous amount of work” that just isn’t physically visible. “The authority is ready to move fast when the money arrives,” he said.

In theory, infrastructure costs should drop after the first phase as construction becomes more efficient, though that’s far from guaranteed, said Goldwyn, the NYU researcher. Some U.S. projects, like LA Metro’s Red Line, saw later phases come in cheaper, but others — such as New York’s Second Avenue Subway — have only grown more expensive. For California’s high-speed rail, costs are expected to climb as construction moves into denser, more complex areas like Los Angeles and San Francisco, he said.

Even so, some over-budget infrastructure projects have delivered major long-term value. Boston’s Big Dig, which buried a central highway underground, was infamously plagued by cost overruns but eventually transformed the city’s urban landscape and boosted the economy. Whether California’s high-speed rail follows that path — or becomes a cautionary tale — remains to be seen.

©2025 The Sacramento Bee. Visit sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments