After killings in Mexico, lawyer seeks help from Chicago attorney -- but Trump-era cuts hamper their work

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — Fifteen years ago, Mexican attorney Alma Barraza immersed herself in a legal fight to win fair compensation for indigent villagers who lost their property when the government seized land to build a dam.

Since then, five villagers Barraza represented were killed. A man she worked with was shot dead, as was one of her bodyguards. Her brother is missing. And who committed the crimes remains a mystery.

Haunted by the lack of answers and stymied by Mexican authorities, Barraza has turned to Chicago attorney John Lee to petition an international tribunal for help in finding the truth and getting justice. But the already difficult journey for Barraza and Lee became more difficult following the Trump administration’s slashing of foreign aid.

With cuts earlier this year and Washington’s further retreat from international aid, reinforced by the $9 billion rescissions package Congress approved this summer and Trump’s $4.9 billion proposed pocket rescission last week, the federal funding that helped pay for Lee’s work was decimated, and the program’s future is uncertain.

The initiative, Justice Defenders, is run by the American Bar Association, which said it received up to $3.4 million annually in federal assistance for the program from the U.S. Department of State. For years, the program has supported lawyers’ work in dozens of countries, shedding light on human rights abuses and strengthening rule of law standards in criminal justice systems. While Lee and other lawyers offered legal services for free, the federal funds helped cover travel, research and other costs.

To Lee, the program represents a civil way, in a post-World War II era, to bring nations together to solve problems and disputes, particularly at a time when “everybody’s trying to pull everybody apart.”

“I believe in the international human rights justice system, and I do my part to help that,” said Lee, who previously worked on a major international case that cleared the name of a Bolivian journalist-turned-politician who battled corruption.

The program is also an example of soft diplomacy that, by aiming to right some wrongs in the world, helps keep other nations more stable and can discourage massive immigration into the U.S., a stated goal of the Trump administration. By rooting out corruption in those other nations, program backers say, fewer people will want to leave.

“If you want to cut down a tree,” Barraza said, “you have to go at the root — so it doesn’t grow back.”

Since the cuts took hold, the ABA and other organizations have filed suit to have some funding for Justice Defenders and other programs restored, stating more than $60 million in foreign aid was earmarked through formal commitments and that the grant funds went for initiatives “related to democracy, rule of law, and human rights.”

The ABA said in its lawsuit that the organization lost grant assistance to fight human trafficking in Colombia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, combat money laundering and terrorism in South America and prepare Ukraine to cope with Russia’s invasion.

A senior U.S. State Department official said in an emailed statement to the Tribune that the Trump administration’s decisions on “any foreign assistance, including for democracy programming, will be guided by whether it makes America safer, stronger and more prosperous.”

But a former State Department employee with the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, who was laid off in early July, said that grants for programs such as Justice Defenders have been targeted because the ABA and other organizations have pushed back against Trump’s foreign aid policies.

“The ABA is on this supposed list of implementers that they simply do not want any foreign assistance ever going to again,” according to the former employee, who spoke anonymously for fear of political retaliation.

Ultimately, the cuts could undermine the efforts of Lee and others who assist foreign lawyers and victims of injustice facing harassment, retaliation and bureaucratic brick walls, from Latin America to Kyrgyzstan and several nations in Africa.

In Mexico, the responsibility for investigating the violence Barraza has witnessed and endured falls to the same government she has repeatedly criticized for inaction on humanitarian crimes. She now hopes to get answers from an international tribunal that could recommend a reluctant Mexico dig further into the alleged crimes.

The Mexican Consulate in Chicago had no comment about the cases of Barraza and her brother.

While the U.S. cuts could hinder Barraza’s ability to get answers, Lee remains undeterred and has already dipped into his own pocket to pay for a trip to Mexico City to consult with Barraza.

“One, I put a decade of my life and work into this, and once I start something, I want to see it successfully completed,” Lee said. “Two, Alma’s courage and Alma’s drive and desire to get justice is also inspiring. She could have left Mexico a long time ago.”

“She will not leave,” Lee said. “I can’t walk away from her either.”

Alma’s ‘miracle’

Alma Barraza’s quest has often put her own life at risk.

Her story, as outlined in interviews with Barraza, Lee and others, in court papers and in news accounts, began in 2010 when a group of residents from rural, small towns around the Pacific coastal city of Mazatlán sought her help after being displaced from their homes to make way for the construction of a dam.

Though they said Mexican officials promised they’d be fairly compensated, dozens of low-income community members said they were shortchanged. The Picachos Dam outside of Mazatlán was built in the state of Sinaloa, a scandal-racked area widely associated with a drug cartel of the same name and plagued by rampant accusations of government corruption.

In 2014, a few years after Barraza, 52, took the case, she said, five members of a family she represented from a nearby village were taken out of their house and executed in front of one another, according to Barraza, news articles and court documents.

That same year, Barraza said radio host Atilano Román, an activist she worked with, was interviewing a woman from a small town near Mazatlán when two gunmen stormed in and killed him during the show. Barraza’s brother, Francisco Barraza Gomez, was kidnapped in 2017 and hasn’t been heard from since, she said.

“Just two months later, they came after me,” she said. “That’s when they tried to kill me.”

One of her bodyguards was killed in a shootout. She said she managed to escape only because of a “miracle.”

For her protection, Mexican authorities moved Barraza from her home in Mazatlán to Mexico City, but she’s often afraid to leave the house. She feels like her personal life and career have been cut short and struggles with insomnia and debilitating episodes of trauma that leave her unable to focus.

Throughout the yearslong ordeal, Barraza was arrested twice while leading demonstrations to bring attention to the villagers’ plight, a saga she said led to her being physically and psychologically abused in jail. Despite offers from the United Natrions to relocate abroad, she remains in Mexico City, committed to defending vulnerable communities.

“She’s tenacious,” Lee said. “She just wants — she wants answers.”

Because Barraza thinks Mexico’s judicial system is “broken” and officials protect corruption in their ranks, she said she connected with him after a U.N. official told the ABA about her plight. The ABA then contacted the New York-based International Senior Lawyers Project, a group familiar with Lee’s work, and asked Lee if he would take on the matter, he said.

Lee, who previously worked on a Latin American case with Texas-based lawyer Arturo Aviles, has once again joined him to file complaints for Barraza with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., that considers international disputes. They hope to bring about a fair and consequential resolution for Barraza, and separately for her brother, that would shed light on the violence and who is behind it.

If a commission recommendation does not spur action, the goal would be to advance both cases to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, hoping to at least push Mexico to seek answers to what happened to the victims missing and killed, according to Lee.

Lee said the Inter-American court’s rulings carry significant weight and could compel Mexico to investigate.

Soft diplomacy

Since 2011, the ABA has assisted over 2,000 human rights defenders in 77 countries, according to a spokesperson for the organization.

Justice Defenders operates with a combination of federal money and in-kind ABA contributions, using the funds to support human rights defenders facing criminal charges, frivolous lawsuits and harassment. About one-third of its efforts have supported lawyers such as Barraza.

But because of the federal cutbacks, the ABA spokesperson said Justice Defenders is shut down in every region except Africa, where it is operating “at a smaller scale” through “private and philanthropic donors.”

At that time of the cuts earlier this year, the State Department still held $1.6 million of the roughly $3 million allocated for Justice Defenders, according to the ABA spokesperson.

Justice Defenders isn’t the only such program providing assistance to human rights defenders that was terminated because of the federal rollback. The ABA argues it was one of the smallest and least expensive, but it had a far-reaching impact.

Defunding this type of soft diplomacy is part of an overarching policy shift in Trump’s White House — a contrast from past administrations that is not lost on critics.

“For generations, the world has looked to America to lead the way to protect civil rights,” said U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee. “That cannot change.”

Durbin said ABA programs funded by the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor “provide critical support to human rights defenders globally and reinforce our nation’s core values.”

Besides Lee, others in Chicago’s legal community continue to engage globally on issues of human rights and justice.

For example, Juliet Sorensen, a clinical law professor at Loyola University Chicago, advised Justice Defenders when it advocated for Kyrgyz Republic journalist Bolot Temirov before several U.N. bodies — including the Human Rights Council and various independent experts.

Temirov was unlawfully deported to Moscow in 2022 in retaliation for his investigative reporting on high-level corruption in the Kyrgyz government, according to Sorensen. He was arrested on what he claims were fabricated drug charges, had his passport annulled, and was later accused of falsely forging documents, she said. He is currently living in exile.

Unlike Barraza’s case, which is before an international tribunal overseeing Mexico and other countries in the Americas, Sorensen and other legal advisers on Temirov’s team petitioned the U.N. in October 2024 to address his case.

His case remains stalled with the U.N. Human Rights Council, which already has a two-year backlog, she said. But she noted the loss of U.S. fiscal support hobbles the effort even more.

While she continues to work on international cases through the Rule of Law Institute at Loyola and maintains her involvement in Temirov’s legal representation, she said the termination of federal funding will limit international legal partnerships.

“Our ability to shine a light on these human rights abuses and to successfully advocate for them … will be severely curtailed,” Sorensen said. “And what happens then? Our collective humanity suffers.”

Past success

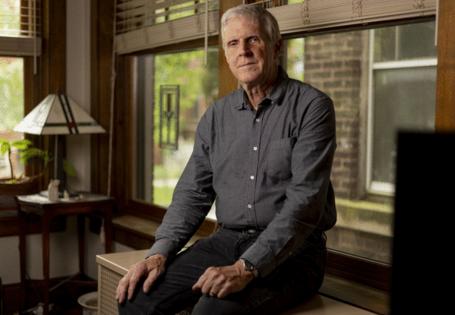

Even though Lee continues to work on Barraza’s case, the 66-year-old no longer practices law full time and instead now primarily teaches environmental classes and lectures about climate change at Loyola University. In addition to a law degree, Lee also holds a master’s in meteorology.

For approximately 25 years, Lee worked on international legal cases to combat injustice and promote human rights, achieving notable success in the high-level world of international courts.

In the early 2000s, he teamed up with his former law school teacher at DePaul University, Douglass Cassel, who had served as the executive director of the school’s International Human Rights Law Institute. An early case they took up was advocating for Lupe Andrade, a former mayor of La Paz, Bolivia, who they claimed was wrongfully accused of corruption.

Andrade was a crusading print and television journalist who won a seat on the La Paz City Council and was later elected mayor. As mayor, Andrade blew the whistle on a contract for a company that developed a tax collection system for the city, a deal her predecessor approved without bringing it before the council, according to a record on the case. But instead of following up on her claims, political opponents successfully pushed to have her prosecuted and wrongly sent to prison, Cassel said.

Andrade got nowhere fighting in local courts, but Cassel and Lee guided her case through the Inter-American commission and courts.

Bolivian officials initially would not follow the commission’s recommendations to clear her name.

“None of them were willing to do it. They were utterly cowardly,” said Robert Gelbard, a former U.S. ambassador to Bolivia who took up Andrade’s cause.

After about 15 years, Gelbard attended Andrade’s 2016 hearings in Costa Rica before the Inter-American court, where Lee and Cassel won a unanimous decision on her behalf, a ruling the Bolivian government finally acknowledged as it “lifted all outstanding measures against her.”

“Lupe got her life back,” said Cassel, now a lawyer based in New York who also has taught at Northwestern University and the University of Notre Dame and worked on complex cases in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador.

“It’s in the interest of the United States to have respect for the rule of law and human rights in Latin America,” Cassel said. “If you don’t, a lot of people flee Latin America and come to the United States seeking asylum. And if they can’t officially pursue asylum, they try to come here any way they can get here. That’s been a bipartisan issue of concern. The more we can make Latin America be a livable place, the less Latin Americans are going to try to come across our borders.”

Barraza echoed Cassel’s point, in a video call from her home in Mexico. Sobbing intermittently, she argued cuts in Washington will do nothing to speed up cases like hers. That’s why she said she’s “deeply grateful” for Lee’s work and dedication to her case.

Gelbard, who sought unsuccessfully to press the Democratic Biden administration to push the Barraza case along, said he worried that a final decision may not come for her until she is “dead or in an old folks home.”

“When the rule of law is perverted, democracy is perverted,” Gelbard said. “And in this case, what we’re seeing is that, by slowing it down, the rule of law is being perverted.”

With U.S. funding cuts slowing development efforts worldwide, pressure builds on each individual case abroad. Cases like Barraza’s show that delays don’t just stall proceedings; they can extend uncertainty and leave lives in limbo.

For now, Barraza waits.

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments