Annunciation principal 'called to show the world what healing looks like'

Published in News & Features

MINNEAPOLIS — “GOD IS GOOD!” the principal shouted to the 300 students buzzing in the auditorium at Annunciation Catholic School. They quieted immediately. “ALL THE TIME!” they responded.

It was two months after bullets flew through the adjacent church’s stained-glass windows, terrorizing students in their first Mass of the new school year. Two children — 8-year-old Fletcher Merkel and 10-year-old Harper Moyski — had been killed, and dozens more injured.

This prayer service marked the first time all students had gathered in one room since their communal trauma of Aug. 27.

The week before, there had been a joyous homecoming for the final injured student returning from the hospital. Yet, signs of heartbreak and stress were all around: panic attacks, nightmare-filled sleep, students who couldn’t make it through the school day. The night before, some students asked parents to walk them through how this prayer service would go. They were scared.

Still, principal Matt DeBoer led with hope.

“ALL THE TIME!” the principal continued the call-and-response. “GOD IS GOOD!” the students replied.

DeBoer had planned this service intentionally, knowing there’s comfort in ritual. He acknowledged that life is hard but said we learn from pain. He prayed for healing. He commended students’ bravery for coming. Praying together is part of their identity, and he wanted these kids to know that hadn’t been taken away.

DeBoer is a Ted Lasso-like character, a 40-year-old whirlwind of positive energy and human kindness. “He hits his alarm clock in the morning and he’s ready to go,” said Kelly Surapaneni, a mentor to DeBoer when he was a Catholic school principal in Seattle.

He repeats motivational phrases to students: “Excellence happens on purpose. So does mediocrity.” He occasionally comes off as cornball (like his embrace of the “6-7″ meme), but his optimism serves as a balm in dark times.

DeBoer sees God’s hand in bringing him to Annunciation to hold this reeling community together.

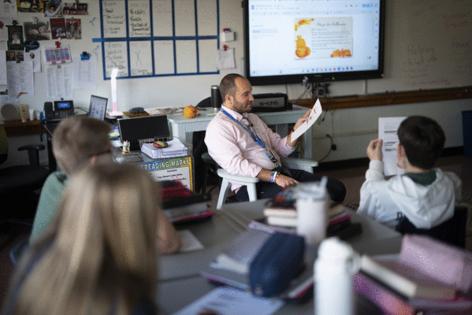

On the morning of the prayer service, DeBoer, with a couple of days’ stubble and the sleeves rolled up on his pink button-up, thought of a children’s book, “We’re Going on a Bear Hunt.”

“We can’t go over it,” the book reads. “We can’t go under it. Oh no! We’ve got to go through it!” Days after the shooting, DeBoer had read the book on Instagram from the school foyer, like a virtual morning assembly. He’d framed it as a lesson in trauma and grief.

This is what going through it looks like: Counselors from the Washburn Center for Children, a community-based mental health agency that’s now a constant presence here, dotted the auditorium. Students clutched stuffed animals like calming therapy dogs. Others wore Taylor Swift-style bracelets with the word “HOPE.” Two children stayed back in the school library, still anxious about an all-student service.

Three eighth-graders recited the responsorial psalm. It was at this point during the Aug. 27 Mass when gunshots burst through stained glass.

“Though I trust in your mercy, let my heart rejoice in your salvation,” read one eighth-grader who’d been shot in the head two months before. Now, her head was partially shaved after surgery to replace part of her skull that had been removed to allow for brain swelling.

Another eighth-grader led a prayer: for government leaders, for Annunciation supporters, for their murdered classmates. “For Harper’s and Fletcher’s families,” she prayed, “may they continue to feel God’s presence and the never-ending love their children have brought. We pray to the Lord.”

Simply by showing up, the students were confronting their darkest memories. Teachers wept.

Classes filed out, singing “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” DeBoer hung back, folding tables and pushing them to a corner. He exhaled, one more rite of passage toward a new normal. The prayer service was like going to the dentist, he said. The nerves were more paralyzing than actually going through it.

“The first time we do anything, it’s hard emotionally,” he said. “But people are reminded — there’s so much joy, right? There’s so much love. There’s so much goodness here. We can do the hard things.

”The grief stuff is so much harder," he continued. “What we do know is that sharing it and grieving together is far more optimal than doing it alone.”

::::

Hours after the shooting in August, DeBoer, flanked by politicians, begged at a news conference that people’s prayers not stop with words. “When you pray, move your feet,” he said, quoting an African proverb.

Watching from his home in Philadelphia, Joe Hejlek, DeBoer’s colleague from a Catholic school in New Orleans, immediately thought of the time DeBoer was mugged.

DeBoer, a teacher at the school, was on his bicycle when three teenagers jumped him. Toppled over in a lawn, DeBoer thought he was about to get shot. He looked the boys in their eyes and shouted, “You’re better than that!”

He was used to working in difficult places. He’d first come to New Orleans on a mission trip after Hurricane Katrina, and he’d served in Ecuador and El Salvador, Appalachia and Ethiopia. Many societal problems, he believed, stemmed from low expectations.

After a tense moment, the boys slinked away. DeBoer called after them: “I have nothing but respect for you! But you’re better than that!”

When Hejlek watched DeBoer, six hours after the shooting, speaking passionately to news cameras and tying his community’s pain and resilience to broader societal issues, Hejlek thought of that mugging.

“Who has the wherewithal to do that?” Hejlek said. “There are some people who in a crisis just get very clear. It’s innate.”

Since the shooting, DeBoer has spoken of being “spiritually chiseled” for this moment.

He grew up going to Catholic school outside Chicago, a basketball captain and high school quarterback. His leadership didn’t always come out in positive ways at first.

In middle school, coping with the awkwardness of adolescence, he was a bully, he said. Two teachers showed him tough love. “‘Are you using your gifts to bring people up or put them down?’” DeBoer recalled them teaching. “It doesn’t take much to flip it.”

Those lessons stuck. His faith blossomed. He started attending Mass by himself. He adorned his locker with Bible verses. He became acquainted with tragedy, realizing from attending five peers’ funerals in high school — either from drunken driving or suicide — that he has a gift to support others in grief. He went to Creighton University, where he aspired to become an inner-city teacher.

As principal, DeBoer echoes his own middle-school teachers’ words when he sees bullying. “You’re a leader,” DeBoer tells students who bully. “Jesus was a leader, and Hitler was a leader. Which way are you going to take people?”

Six times after Katrina, he went to New Orleans on college mission trips. Then, after meeting his future wife on a mission trip to Ethiopia, he moved to New Orleans with the Jesuit Volunteer Corps.

“In New Orleans he found a devastation he’d never seen before, but in the midst of that, so much joy and celebration and community,” said his wife, Rose DeBoer. “That was something he yearned for.”

His path led to Seattle, where he began as a Catholic school principal at age 28, then to Minneapolis as campus minister at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School.

But his heart was with younger kids. “I call it preventative medicine,” he said. “After dealing with all the high school behavior, let me get ahead of this curve.”

DeBoer’s values are simple enough to distill for youngsters: Be kind. Seek justice. Treat others how you want to be treated.

On Aug. 27, soon after the shooting stopped, DeBoer walked outside the church and saw the shooter’s lifeless body. He wanted to attack that body. Instead, he prayed, echoing Jesus on the cross: “Father, forgive him, for he knows not what he did.”

Later that morning, students gathered in the school gym to reunify with their families. They recited the Lord’s Prayer. For DeBoer, hearing part of that prayer — “as we forgive those who trespass against us” — was hard. “We were so trespassed against,” he said.

But then he saw a police officer in SWAT gear, tears streaming down his face as he prayed alongside students.

“To see that, and to be able to look out at everybody — we’re going to get through this,“ he recalled.

::::

DeBoer counts five days as the most joyful moments of his life: his wedding day, the births of his three children, and the October day when Sophia Forchas, the gravely injured seventh-grader who for weeks teetered between life and death, stepped out of a limousine in the school parking lot and was enveloped by friends.

A doctor called her recovery a miracle. DeBoer called it a “resurrection moment.”

“I don’t know how anyone cannot believe in the divine when you have a story like this,” DeBoer said. “You have moments of joy like that. And then I’ve been to two children’s funerals. What we want to continue to talk about is the lives Harper and Fletcher lived and how they lived them and the joy they put on this Earth. We were invited to continue to be the light.” He was referencing a moment from Harper’s funeral, when her mother beseeched people to carry Harper’s light forward. “It’s our job to carry that torch on,” DeBoer said.

DeBoer did not sleep for 40 hours after the shooting, pacing all night. During the shooting, he had thought: “I’ll protect these children by any means necessary.” Now he felt consumed with guilt that he hadn’t protected all of them. The next morning, his watch showed he’d walked 24,000 steps.

In hours of interviews with the Minnesota Star Tribune, there was only one point when DeBoer broke down. He was talking about how the shooting changed his students. Some kids who were never afraid of the dark or of sleeping in their own room now are. Some worry about sitting near windows.

“It’s a reminder of what was taken from us in addition to Harper and Fletcher — which is the innocence of children,” he said through tears. “The ability to go to school and laugh and be yourself has been stolen because of a horrific act.”

And yet he sees hope. DeBoer worried the school’s enrollment would be halved after the shooting, but all but two kindergarten families returned, along with the entire staff. DeBoer has received thousands of letters from around the globe. Every Catholic school in the Archdiocese of Seattle is doing a project supporting Annunciation. Students at DeBoer’s alma mater outside Chicago wear Annunciation T-shirts every Monday.

On the two-month anniversary of the shooting, he led Washburn counselors through the church to better understand how the shooting transpired. He told of blood spattered on a rendering of Jesus on the cross, and he recounted how the thick wooden pews served as lifesaving barriers.

Friends and family worry DeBoer isn’t prioritizing his own healing. He did take a 40th birthday trip to see friends and a Jon Batiste concert in Philadelphia. And his family took a Thanksgiving trip to Florida.

The job is all-consuming. He greets kids in the morning drop-off line with a boombox. He coaches the sixth-grade basketball team after school. He teaches weekly ethics classes to eighth-graders. He’s focused on building an inclusive community, which is what this moment demands.

DeBoer helped choose the language on the back of the Annunciation T-shirts made after the shooting. “Be the light,” reads one phrase. “Together we heal,” reads another.

“It’s not what I signed up for, but it’s what I’m called to do,” DeBoer said. “We’re called to show the world what healing looks like, and that it doesn’t happen in a month or a year. It’s a lifetime’s work to be the light. There are times we need to lock our doors and cry it out. But ultimately healing comes from community.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC ©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments