Entertainment

/ArcaMax

Ethan Hawke thinks his Blue Moon Oscar nomination is a full circle moment

Ethan Hawke feels as though his latest Oscar nomination is a full circle moment in his career.

The 55-year-old star has been nominated in the Best Actor category at next month's Academy Awards for his part in Blue Moon and reflected on the quarter of a century that has passed since he was first recognised for his work in the 2001 film Training ...Read more

Susan Sarandon claims she was exiled from Hollywood for speaking out about Gaza war

Susan Sarandon says she was blacklisted in Hollywood after speaking out about the Gaza war.

The Thelma and Louise star was dropped by United Talent Agency in 2023 for calling for a ceasefire in the conflict and claims that it "became impossible" for her to land film and TV roles in the United States as a result.

Speaking at the Goya Awards ...Read more

'I'm an incredibly average person': Cillian Murphy is not interested in Hollywood attention

Cillian Murphy thinks he is "an incredibly average person".

The Peaky Blinders star has little interest in Hollywood fame and confessed that he is "really bad" at being on the red carpet and giving interviews about himself.

Cillian, 49, told The Times newspaper: "Being a personality is not what I am good at.

"But then existing in this world? ...Read more

Legendary singer Neil Sedaka dead at 86

Neil Sedaka has died at the age of 86.

The singer-songwriter - who was best known for hits including Breaking Up Is Hard to Do, Oh! Carol, Calendar Girl, and Happy Birthday Sweet Sixteen, as well as writing songs for the likes of Connie Francis, The Monkees and ABBA - was hospitalised on Friday (27.02.26) morning and died later in the day, ...Read more

Thomas Rhett is a dad again

Thomas Rhett has become a father for the fifth time.

The 35-year-old country singer and his wife Lauren Akins - who already have daughters Willa, 10, Ada, eight, Lennon, six, and Lilie, four together - welcomed son Brave Elijah into the world last week and the Die a Happy Man hitmaker has been praised by his spouse for helping to "deliver" the...Read more

How 'hero' Benny Blanco stopped Selena Gomez's tears before their wedding

Selena Gomez was in tears in the days leading up to her wedding after losing her handwritten vows.

The Only Murders in the Building actress married producer Benny Blanco last September and while things went smoothly on the big day, there was a hitch beforehand when she misplaced her notes for four or five days.

But fortunately, Benny saved the...Read more

Robert Carradine's cause of death confirmed

Robert Carradine's death has been ruled a suicide following his passing earlier this week.

The Lizzie McGuire actor - who had battled bipolar disorder for decades - died at the age of 71 on Monday (23.02.26), and online records for the Los Angeles Medical Examiner's Office listed the cause of death as being due to anoxic brain injury, where the...Read more

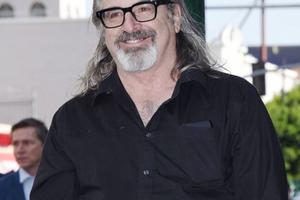

Jason Blum wants to keep budgets low

Jason Blum wants to keep making "super-low budget movies".

The horror producer - who has over 200 credits to his name - recently merged his Blumhouse company with James Wan's Atomic Monster, but just because he can now make "more expensive" films as a result, Jason doesn't want to turn away from the smaller work he is known for.

He told The ...Read more

Ryan Gosling hails 'once-in-a-lifetime' project Star Wars: Starfighter

Ryan Gosling has hailed Star Wars: Starfighter a "once-in-a-lifetime opportunity".

The Project Hail Mary actor leads the cast of the upcoming stand-along story and has explained why big franchise projects had "never felt right" to him until director Shawn Levy pitched the project - which also stars Amy Adams and Mia Goth - and he was blown away...Read more

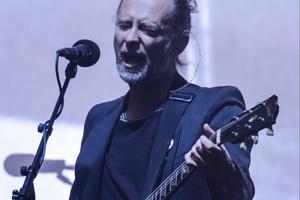

Radiohead issue furious statement to ICE

Radiohead have been left infuriated after a cover of their song Let Down was used by ICE.

The Paranoid Android hitmakers have issued a blunt statement condemning the US Department of Homeland Security after a choral version of the song, which appears on their 1997 classic album OK Computer, could be heard in the background of a social media ...Read more

Billy Idol shares measured response to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame shortlisting

Billy Idol has insisted there is no guarantee he will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The Rebel Yell hitmaker was announced this week as one of 17 nominees for this year's honour, but after failing to make the cut on his first nomination last year, he doesn't see his induction as a foregone conclusion.

He told Billboard: "I ...Read more

Singer Neil Sedaka dies suddenly at 86

Iconic singer-songwriter Neil Sedaka has died suddenly at 86, his family announced on Friday.

The Brooklyn native was taken by ambulance to a Los Angeles area hospital Friday morning because he wasn’t feeling well, according to TMZ. He died a short time later, though his cause of death is currently unclear.

“Our family is devastated by the...Read more

Pink 'has moved to New York and is in running to take over Kelly Clarkson's talk show'

Pink is said to have moved to New York and is said to be in the running to take over Kelly Clarkson's NBC talk show.

Amid reports about her marriage that she has publicly denied. the singer, 46, who has spent recent years living on her vineyard on California's Central Coast, has sparked rumours about her career after being seen back in the city...Read more

Paris Jackson shares rare photographs with her mother Debbie Rowe

Paris Jackson has shared rare photographs with her mother Debbie Rowe.

Posting intimate images to social media offering a glimpse into their relationship years after they reconnected, Michael Jackson's daughter, 27, uploaded two images to her Instagram Story featuring Debbie, 67, the nurse who was married to Paris's father, Michael Jackson, ...Read more

Neil Sedaka 'hospitalised after falling ill at his home'

Neil Sedaka has reportedly been hospitalised after apparently falling ill at his home.

The 87-year-old singer is said to have been taken by ambulance for treatment on Friday (27.02.26) morning, and was apparently transported from his residence at about 8am after feeling unwell.

According to TMZ, who first reported he had been hospitalised, he ...Read more

Singer Neil Sedaka dies at 86

Legendary singer-songwriter Neil Sedaka has died at 86, his family announced on Friday.

The Brooklyn native was taken by ambulance to a Los Angeles area hospital Friday morning because he wasn’t feeling well, according to TMZ.

He died a short time later, though his cause of death is currently unclear.

“Our family is devastated by the ...Read more

'Racist!' shout disrupts Brigitte Bardot tribute at French awards show

A shout of “Racist!” was heard at France’s 51st Cesar Awards during a tribute to actress Brigitte Bardot.

There were also cheers mixed with boos as the “And God Created Woman” star’s famous face closed out the segment on Thursday night.

At least one person could be heard insulting the outspoken conservative, who died from cancer in...Read more

Backstreet Boys add 6 more summer dates to Sphere residency

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Due to fan demand, the Backstreet Boys have added six more summer dates to their Into the Millennium residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas.

The newly announced shows will take place July 30-31 and Aug. 1, 6-8, following previously announced performances on July 16-18 and July 23-25.

Tickets for the added shows are available ...Read more

Joji announces Solaris Tour

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Fresh off the release of his new album, Joji is taking the music global.

The singer and producer has announced the Solaris Tour, a sprawling international arena run that will include a July 11 stop at the Intuit Dome in Inglewood.

The Live Nation-promoted tour will span North America, Europe, Asia, Australia and New Zealand...Read more

KLOS-FM host Uncle Joe Benson, one of LA radio's legendary voices, dies at 76

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Radio disc jockey Uncle Joe Benson, whose deep voice rumbled over the airwaves of KLOS-FM, Arrow 93.1, and The Sound 103.1 for nearly four decades, died Tuesday, Feb. 24. He was 76.

“It is with great sadness that we share the news of legendary disc jockey Uncle Joe Benson’s passing,” read a post on the Uncle Joe’s ...Read more

Inside Entertainment News

Popular Stories

- Singer Neil Sedaka dies suddenly at 86

- Katherine Short 'found dead behind locked bedroom door with suicide note and gun nearby'

- Pink 'has moved to New York and is in running to take over Kelly Clarkson's talk show'

- 'Racist!' shout disrupts Brigitte Bardot tribute at French awards show

- Paris Jackson shares rare photographs with her mother Debbie Rowe