Review: In Broadway's 'Gypsy,' Audra McDonald invites a spiritual epiphany

Published in Entertainment News

NEW YORK — A funny thing happened on the way to being blown away by Audra McDonald in the new Broadway revival of "Gypsy." For much of the production, directed by George C. Wolfe, I was quibbling and quarreling with the reigning queen of Broadway.

I expected to be agog, because whenever McDonald is on stage, no matter if it's a musical, play or concert, my appreciation for the majesty of her brilliance soars. But in "Gypsy," I felt strangely aloof from her performance for a good portion of the production. Heresy to admit it, but I questioned some of her choices and even doubted whether the role of Rose was an ideal fit for the Broadway performer I hold above all others.

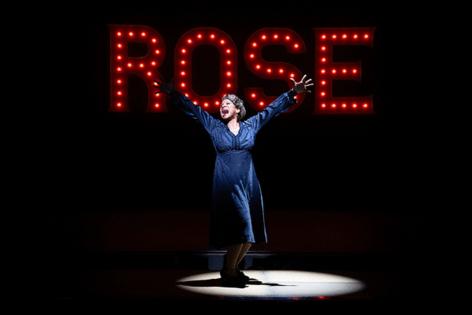

But then something miraculous happened, "Rose's Turn," the show's shattering finale, and the path McDonald had been forging as Rose all along suddenly became transcendentally clear. It wasn't simply that the actor's virtuosity was unleashed at full force. It was that Broadway history and Black American history were converging in a performer who was offering her gifts to an audience in a climactic conflagration.

The result was, if not a religious experience, then a spiritually transfiguring one. There was something at once sacrificial and redemptive in what McDonald was channeling in her art, and I left the Majestic Theatre feeling reborn.

So what was I caviling about to myself during intermission? Believe me, I'm not in the habit of second-guessing this six-time Tony winner (a record for a performer, who has incredibly won in every acting category). Awe-struck is my accustomed state when McDonald is on stage.

But "Gypsy," the canonical 1959 musical by Jule Styne (music), Stephen Sondheim (lyrics) and Arthur Laurents (book), brings with it a raft of expectations. The show is settled law that McDonald and Wolfe are bold enough to unsettle.

It's not that she's unfaithful to the material. She adheres both to the letter and the spirit of the original material. She's just not interested in replicating anyone else's idea of the character. Admittedly, it took me some time to put my previous Broadway Roses behind me.

While taking in McDonald's performance, I was fondly recalling the blunt, blue-collar realism of Tyne Daly's portrayal in Laurents' 1989 production. And harking back to Sam Mendes' polarizing 2003 revival, I wistfully reflected on the broken-doll quality that Bernadette Peters brought to a character formed in the battleship mode of Ethel Merman, the original Rose.

As soon as the orchestra began playing the overture, the blazing showmanship of Patti LuPone came rushing back to me from her performance in Laurents' 2008 production. LuPone, whose native gifts and career trajectory destined her for triumph, would be my desert island Rose, if I could bring just one.

All revivals of "Gypsy" are haunted by the long line of illustrious predecessors. Starring in "Gypsy" comes with as much baggage as playing Stanley or Blanche in Tennessee Williams' "A Streetcar Named Desire."

But no actor had it harder than Angela Lansbury, who was in the first Broadway revival after Merman patented the role. Lansbury had little in common with Merman, so she had to take the character in a new direction, which critics, such as Walter Kerr, admired for the dramatic depth it unearthed.

Of course every actor must remake Rose in her own image. But McDonald is attempting something far more radical, incorporating her full historical self as a Black woman to serve the musical's recontextualization.

Rose, the archetypal stage mother determined to launch her daughters into the spotlight she was denied, is hustling June and Louise on the vaudeville circuit in the 1920s through the early 1930s. But she's doing so here as an unmarried Black woman with all the unspoken freight that entails.

What was I initially resisting in McDonald's portrayal? It had nothing to do with what was bizarrely controversial before the production opened — the casting of a Black actor in the role.

Last June, John McWhorter wrote a New York Times op-ed column that took issue with the idea of a production reconceiving Rose as a Black character. "In 1920s America, when the show is set, racism and segregation remained implacable forces in popular culture, and the only stardom a Black Rose would have realistically sought for her kids would have been among Black audiences," he wrote.

His issue wasn't with McDonald but with the proposed approach. "A talent as rare as Audra McDonald shouldn't play a Black Rose," he asserted. "She should just play Rose."

When asked to address McWhorter's column, McDonald gently pointed out that the original full title was "Gypsy: A Musical Fable" to clarify that, though based on the memoirs of Gypsy Rose Lee, the musical is a fictional work that freely strays from the historical record. McWhorter recanted after seeing the production in a column titled "I've Changed My Mind. Audra McDonald Was Right" that touted the star's "spellbinding" artistry and predicted that she would go on to win her seventh Tony.

The qualms I was registering during intermission were unrelated to McWhorter's history-laden concerns. My cognitive dissonance stemmed from theatrical considerations. I wondered about the suitability of McDonald's vocal style and questioned her comfort level with broad comedy.

Now who in their right mind could have an issue with McDonald's singing? I am second to none in my reverence for her lyric soprano. But Rose is a belter, or at least that is how her musical numbers have been traditionally performed. When McDonald's Rose sings, on the other hand, you hear a classically trained singer with extraordinary vocal resources.

At moments her Rose sounds as if Carnegie Hall was her bygone dream for herself, not the vaudeville circuit. Styne and Sondheim's score is hardly a monolith. Comic pastiche gives way to tender romantic ballads only to explode in musical psychodrama.

In "Small World," Rose's early number with Danny Burstein's Herbie, the unattached man she latches onto as an agent for her kids, McDonald offers a glimpse not only of the heart behind all the relentless calculation and striving but also of an Olympian talent waiting to blow the competition out of the water. Psychologically, it works. But the exceptional nature of McDonald's gifts strikes an incongruous note.

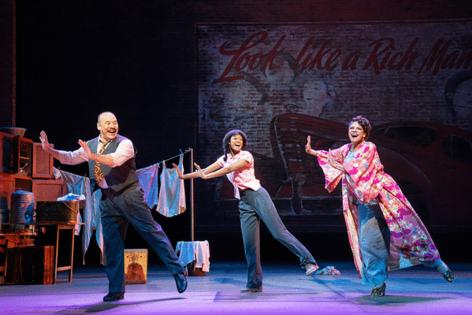

The beauty of McDonald's voice doesn't dissolve into the character but retains a kind of formality. You can hear this decorous quality in Rose's subsequent number with Herbie, "You'll Never Get Away From Me," as well as in the determinedly jaunty "Together, Wherever We Go," which brings Rose, Herbie and Joy Woods' Louise momentarily into frolicsome solidarity.

The sophisticated shadings of McDonald's singing are of a piece with the character's slightly affected manner of speech. I confess to having a little trouble placing this Rose. But what I worried might be a natural discrepancy between performer and role turned out to be an integral part of McDonald's character. It just took me some time to see how.

Wolfe leans into the revue-sketch nature of this backstage comedy. "Gypsy" has been called the "King Lear" of musicals for the capstone tyrannical parent role it provides an actor of a certain age. But the show's zany side has more in common with one of Shakespeare's early rollicking comedies — "The Taming of the Shrew" en route to becoming "Kiss Me, Kate," perhaps.

McDonald is game for the high jinks but doesn't always seem natural gamboling about the stage. A slightly awkward cutup, she betrays some of the same resistance that Louise has shown when thrust against her will into yet another inane kiddie act.

It wasn't until "Rose's Turn" that I realized — with the force of a crushing epiphany — that all of this was intentional. That it wasn't McDonald's mismatched qualities on display but the reality of a Black Rose who has had to adapt herself in constricted ways until better opportunities come her way.

The finale, a musical nervous breakdown, illuminates what's been driving the character all along. Here, it breaks the facade that McDonald's Rose has had to erect to get through life. The careful enunciation, the singing voice that could soar to sublime heights but can't call too much attention to itself, the unwavering dreamer chasing after paltry show business leftovers — McDonald embodies the social reality of her character's compromised choices in the way she shrinks and swells Rose's very being.

The anguish that erupts during this "Rose's Turn" represents more than the built-up sorrow of one embittered woman. It holds the grief of ancestors denied their shot. McDonald's performance opens a window onto the grandmothers and great-grandmothers whose lives were even more tragically curtailed.

Never have I experienced a performance come into such searing retroactive focus. The catharsis of "Rose's Turn" is also a fulfillment. In "Gypsy," McDonald augments her unparalleled Broadway legacy by summoning America's rueful history to the stage.

________

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments