Nina Metz: Teen movies used to be a genre Hollywood took seriously, young audiences too. But good luck finding them in theaters today

Published in Entertainment News

Executives at Walt Disney studios are asking Hollywood creatives for movies aimed at teenage boys, according to recent reporting in Variety. On one hand, this is hilarious. Since at least the 1980s, movie studios have been fixated on catering to an audience of teenage boys. This is not a new concept.

On the other hand, teen films as a genre — most of which were geared to all kids, regardless of gender — are a casualty of the changing business model brought on by streaming, as studios have abandoned mid-budget films to focus almost exclusively on blockbusters.

I can’t think of a single teen movie that’s played in theaters this year. Does “Freakier Friday” qualify?

Not really, according to Jacqueline Johnson, a teaching associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh. The 2003 version of “Freaky Friday,” starring Jamie Lee Curtis and Lindsay Lohan as a mother and daughter who switch bodies, is pretty close. But this new one? A stretch. “Teen movies aren’t just about teenagers, but they are catering to that audience. And ‘Freakier Friday’ is really for people like me, because the first one was a really big deal to me when I was younger. But I’m 32.”

Johnson is teaching a course this semester focused on teen films. By default, it is also a history course, because while there are plenty of TV shows aimed at teens — from HBO’s “Euphoria” to Amazon’s “The Summer I Turned Pretty” — when it comes to movies getting a theatrical release, the cupboard is bare. Why does that matter? Because these movies tackled all kinds of worthwhile themes and were made specifically with teenagers in mind to see together.

“I have such a visceral memory of going to the midnight premiere of ‘Twilight’ when I was in high school,” said Johnson. “So it wasn’t just that these movies existed, there was also a social thing around going to movies as teens.” It was a way to get out of the house, and you could do without an adult.

The moviegoing habit has diminished, but according to Johnson, “the social aspects have migrated to online platforms. I went to Reddit to see what people were saying about the final season of ‘The Summer I Turned Pretty’ and it was on fire with the weekly discussions and memes. So I feel like the social aspect of going to the movies has migrated to digital spaces.”

Arguably, one of the earliest teen movies dates from 1920. The silent film “The Flapper” follows the antics of a happily rebellious 16-year-old sent to boarding school to reform her ways, only to see her thwart those efforts at every turn.

But the idea of teenagers as their own demographic — as people with experiences unique to their stage of life, with unique consumer interests to match — didn’t take root until after World War II. An analysis in the Saturday Evening Post calls it “one of the more unusual inventions of the 20th century.” And you’d better believe that Hollywood took notice.

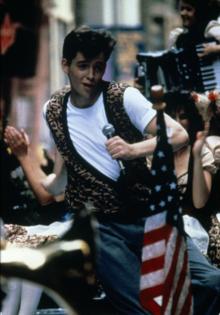

The films Johnson has selected for her class span the decades, including 1986’s “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”

“I chose that one out of all of John Hughes films because I’m interested in the way it breaks the fourth wall (when Ferris talks to the camera) and I thought that would be a good jumping off point to think about the way the movie enters the teen psyche. Young people already watch so many mockumentaries and spend so much time on TikTok, and ‘Ferris Bueller’ uses some of those same ideas, but as a formal device.” I hadn’t thought about it that way, but she’s right.

Teen movies often exist in the popular imagination as comedies. But many are not, including 1955’s “Rebel Without a Cause” starring, among others, Natalie Wood and James Dean. It’s a story of suburban teens who are lost and unmoored, and in conflict with (or neglected by) their parents. Johnson is including the film because “as the algorithm structures more and more of our media lives, I feel like a lot of younger adults are even further divorced from the past than ever, and I really want people to understand the genre’s history and that the teenager is a created identity in postwar culture.”

But she’s also focusing on titles that I didn’t immediately categorize as teen movies, even though they are, such as the 1978 horror film “Halloween.” The phrase “teen slasher” exists for a reason. Is this subgenre tapping into specific anxieties that other horror films are not?

“A lot of teen horror films are invested in these worlds where the adults around you are not going to help,” Johnson said. “One thing that’s so interesting about ‘Halloween’ is that this type of community — the suburbs — is supposed to be safe. It’s middle-class. It’s white. But as Jamie Lee Curtis is running through the streets, pounding on people’s doors to get somebody to help her, nobody does. So the teen horror movie also often thinks about the logics of suburbia, of whiteness, and of the nuclear family in interesting ways.”

Thematically, most teen movies tackle ideas around social hierarchies, sexuality and gender roles. The comedies do this handily. (Johnson’s list also includes “Heathers,” “American Pie.” “10 Things I Hate About You,” “Hairspray” and “Easy A.”) But another drama she’s focusing on is 2011’s “Pariah,” about a Brooklyn teenager who gradually comes into her lesbian identity.

“So many teen films are about white people and made by white people and this allows us to expand the vision for what a teen film can be, which also includes the queer teen film and the independent film. ‘Pariah’ is really interesting to me because the core theme of the teen movie is a teenager coming into being and figuring out who they are, and this narrative fits that so well.”

Teen movies are made by adults looking back and filtering the story through their own memories and experiences. So how much was Hollywood really capturing the teen experience versus codifying it? The popularity contest of high school tends to fall away for many people once they graduate. But maybe, Johnson said, social media has extended that phenomenon.

“I’m really interested in how teens document themselves outside of the traditional Hollywood system. And social media ‘likes’ — with its ideas about visibility and who should be visible — really do map on to some of these hierarchies in teen films.”

———

(Nina Metz is a Chicago Tribune critic who covers TV and film.)

———

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments