Review: 'The American Revolution' presents a fresh picture of America's complex founding

Published in Entertainment News

Back in 1990, Ken Burns made his reputation with "The Civil War," a sprawling, mutlipart documentary that caused a sensation, set a standard and sealed the style he's applied to practically everything he's done since — measured and hypnotic (some would say slow), with photos and paintings scanned for revealing detail, actors reading primary documents and, more likely than not, the voice of narrator Peter Coyote guiding you through.

With the six-part "The American Revolution," premiering Sunday and continuing nightly through Friday on PBS, Burns' longtime home, he has created a sort of prequel to that series, looking at a war for independence that was also a civil war and in which enslaved Black Americans and Indigenous peoples played a part. Burns has crossed this subject before, with films dedicated wholly to Thomas Jefferson (1997) and Benjamin Franklin (2022), not to mention series on Vietnam and the Second World War. But this is foundational stuff for a filmmaker specializing in American figures, institutions and events — the Dust Bowl, Prohibition, women's suffrage, baseball, the buffalo, Muhammad Ali, the Central Park Five, Frank Lloyd Wright, the National Parks and Mark Twain. In the history class of my mind, his films comprise the syllabus.

Burns, co-directing with Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt, is not an academic, but he knows how to marshal those troops. His gathered historians and scholars, including women, Black Americans and Native Americans, come at the subject from different angles, some with special areas of expertise. Along with letters, memoirs, speeches, pamphlets and newspaper extracts read by a cast that includes Meryl Streep, Kenneth Branagh, Morgan Freeman, Claire Danes, Matthew Rhys, Edward Norton, Michael Keaton, Laura Linney, Craig Ferguson, Samuel L. Jackson, Tom Hanks, Adam Arkin, Damian Lewis, Keith David and Paul Giamatti, once again suiting up as John Adams, they present a complex picture of a story often obscured in red, white and blue certainties. Burns and company are not aiming to present a neat picture; if they were, "The American Revolution" (written by frequent collaborator Geoffrey C. Ward) would not last 12 hours.

The revolution's greatest hits are all here, from petitioning the king of England for a redress of grievances to a Declaration of Independence. The Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party ("They dressed like Indians, kinda," says Native American author Philip Deloria), the midnight ride of Paul Revere, Thomas Paine publishing "Common Sense," the Declaration of Independence, George Washington crossing the Delaware, Bunker Hill, Benedict Arnold (he was very good before he was very bad, but touchy), John Paul Jones and Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, 19 years old and looking for action. French money and the French navy were crucial to the American victory. All are presented in a way that freshens even what you know, or think you do.

The point is made, not for the first time, that for women, slaves and natives, the hope that liberty would be more liberally applied was not fulfilled. African Americans fought with the colonists at Lexington and Concord, the very beginning of the war, though three times as many more would join with the British, who seemed the better door to freedom, but slaves were returned by the victors to their masters. (White colonists used "slavery" to describe their own position vis-à-vis the English, without irony.) "For us, the Mohawk people, it was survival, period," says historian Darren Bonaparte, "and you didn't know which side was going to be the best choice." We know how that history went. Women carried bodies from the battlefield, oversaw their burial and got the vote in 1920.

Things go this way and that; fortunes reverse and reverse again. The war, and what could go on around the war — sexual violence, vigilantism, thievery, arson — was exceptionally violent, a violence Burns does a good job of communicating. Not only armies but whole civilian populations were on the move, depending on what side they were on. Among the American troops, there were mutinies and desertions and soldiers simply going home when their enlistment was up. (Nobody was getting paid, anyway.) During a hard winter at Valley Forge, which became for a time the fourth largest city in America, Washington was not always confident in his army's survival, writing that his men would soon be "reduced to one or the other of these things; starve, dissolve or disperse in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can." We know how it turned out, of course.

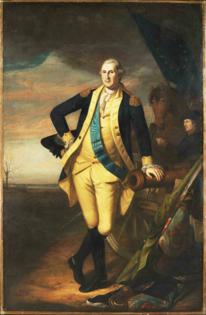

What distinguishes "The American Revolution" from other Burns works is its emphasis on the progress of war, battle by battle, with old maps and new 3D maps overlaid with arrows and lines and blue and red bars to represent the movement and position of colonial and British armies. Contemporary battlefield sketches, grand postwar history paintings, elegant portraits of the major military and political figures, along with watercolor illustrations and unobtrusive live-action recreations bring the tale to life.

As in other Burns projects, the narrative is knit together out of many individual stories, but it's Washington, the commander of the army, who stands out here — as he literally did in life, measuring 6 feet 3 when the average height was 5 feet 7. Described here as the "glue" that held the not-quite-country's factions together, his enumerated blunders as a tactician were mitigated by his effectiveness as a leader; he could change the course of a battle merely by appearing on the field.

That Washington owned slaves (a lot of them), as did Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, is well-known; that, as one of America's wealthiest men, he speculated in Indian land (as did Jefferson, Franklin and Patrick Henry) was new to me, as was his ordering the complete destruction of the villages of the British-allied Seneca and Cayuga — "You will not by any means listen to any overture for peace, before the total ruin of their settlements is effected." In the words of historian William Hogeland, he had "a ruthless and intense focus on his own interests, which makes him exactly like every other member of his class; it's just that he became George Washington."

On the verge of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, when it seems that the democratic project may be going down the tubes, the demagoguery against which the founders warned has become the order of the day, and war is being waged on settled history, as ideological functionaries draw a curtain over whatever might make MAGA feel bad, "The American Revolution" stands its ground. And fundamentally, it's a celebration — our less perfect union has made it this far, so far.

———

'THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION'

Rating: TV-14

How to watch: Premieres Nov. 16 at 8 p.m. ET on PBS

———

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments