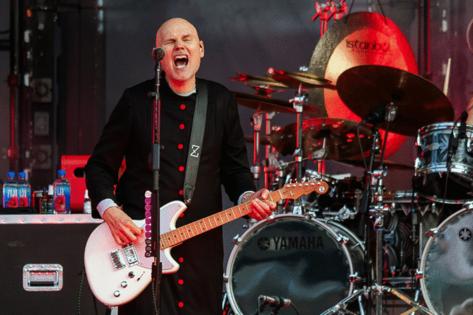

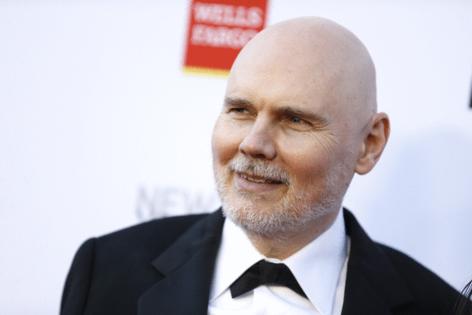

Q&A: 'Nothing was quite the same after that': Smashing Pumpkins' Billy Corgan relives 30 years of 'Mellon Collie'

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — It was early 1996, and a young alternative band known as the Smashing Pumpkins was embarking on a worldwide tour for their newest album, “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness.” One of the first stops of the tour was Los Angeles, for a sold-out show at the historic Palace Theatre packed with screaming fans. They began the set — contrary to the noisy atmosphere of the year prior characterized by distorted alternative rock — with a piano solo.

It’s the album’s opening title track, a poignant, emotional tune woven with promise and the start of something new. It was written by then-28-year-old front man Billy Corgan as he learned to play piano for the first time.

It was like being caught in a dream, between the theater’s velvet curtains, the sweet instrumental and the excited cheering audience, Corgan remembers. Then, the crashing, jagged sounds of drums and electric guitar filled the room, and the sonic experience of “Mellon Collie” unfolded.

Thirty years later, “Mellon Collie” is recognized as one of the most influential rock albums of the decade, later cited as inspiration by later acts like Muse, My Chemical Romance and Silversun Pickups. Its release was a significant shift for the band, which had been known for dreamy prog-inspired rock on their previous hit 1993 album “Siamese Dream.” In contrast, “Mellon Collie” was an experimental concept double-album with lyrics following a journey that Corgan explains as “one day that can represent your entire life.”

In this concept, the day evolves through heavy, distorted explorations of identity and anger in “Muzzle,” “Zero” and “Bullet with Butterfly Wings,” whimsical, twinkling memories in “Cupid De Locke” and “Thirty-Three,” and love and adolescence in “1979” and “Love.” The wide scope of the album, both in subject and sound, made it an ambitious and unique among rock releases of the time, shedding the humble irony of the grunge movement for vulnerability and exploration.

Inspired by Pink Floyd’s “The Wall,” Sonic Youth’s distortion, Black Sabbath’s symbolic lyricism and layered instrumentals, and surrealist artwork, “Mellon Collie” tested the Smashing Pumpkins’ limits as a band. It asked of them: How expansive could they become, and how could they translate the human experience into the form of an album?

For the 30th anniversary, the band is collaborating with their hometown orchestra, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, to bring “Mellon Collie” to life in an opera form. They’re also reissuing the album with previously unreleased recordings from that 1996 “Infinite Sadness” tour. With sets from the Los Angeles performance to Philadelphia, the recordings capture the rawness of their performance and a pivotal moment for the band’s history.

In “Tonight, Tonight,” Corgan reminisces, “And our lives are forever changed, we will never be the same.”

In the scope of “Mellon Collie,” his words are eerily true. “Nothing was quite the same after this album,” Corgan told the Times. And in truth, nothing was.

The album accrued seven Grammy nominations and shot the band into rock stardom with long-lasting singles and heavy MTV airplay. But behind the scenes, Corgan was going through the divorce of his first marriage. In the midst of heartbreak, the album’s tour broke open tensions within the band, culminating in a breakup after the overdose death of touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin. Corgan’s mother passed away later that year.

What came shortly after “Mellon Collie” and the fateful 1996 tour was nothing short of chaos. But in the brief moment of the album came a delicate and harmonious collaboration between Corgan and the Smashing Pumpkins to create an album that would define their careers and, in some ways, their lives.

Q: Something I really love, especially about the piano and “Tonight, Tonight” as the opening track, is this feeling of hope that it starts off with, or maybe that’s just what I got from it.

A: [Laughs] It starts with hope and ends somewhere else, let’s put it that way.

Q: What was the intention with starting with this feeling and what was it inspired by at the time?

A: I was going through a lot in my personal life, and I was grappling with the changes in my life and the awareness that I had in my life, given what I’d been through as a child and now as an adult with success, it was like I was trying to grapple with all that and wondering what really matters.

I think if you look at the general narrative of the album, it starts with the idea and it starts with the dream and what is possible within the dream. So, for example, you pointed to the piano piece that opens the record.

I went to a store, not too far from where I’m sitting and talking to you [he was calling from his car in Chicago], and bought an old 1920s piano with mismatched legs for $2,500. Now that may not seem like a big deal, but at 27 years old, when I was writing the record, I never owned a piano nor was I allowed to play a piano in my relatives’ houses.

So I finally had this moment of, wow, I can actually buy a piano and I can play my own piano in my own house. As silly as that sounds, it had never crossed my mind that way. I’d always lived in apartments and I was always on the road. It was like a new beginning. It starts with the gift that I gave myself and that ends up having a lot of influence on the compositional structure of the record.

And then “Tonight, Tonight,” was a song that we messed around with for about four months. And one night it just came to me in a flash, like what the song needed to sound like, and I went upstairs to this room that I had in my house and I just remember playing it like I could hear the whole orchestra in my head and I thought, OK, that’s what I need to do.

Q: Something I see on this new reissue is that there’s going to be a lot of recordings from that live 1996 tour right after the release of the album. What was it like relistening to these performances, especially as it was the last tour with the band’s full original lineup?

A: We had crested a particular wave at the time. We had a No. 1 album. We were playing, I think, a 90-date arena tour, which, now there’s a ton of artists playing stadiums, but back then an arena show was essentially the top of the mountain. So then we had success, we had fame, we had money that we’d never had.

With that, we had all the trappings. And I think in the recordings that are on this record that’s coming out, it’s like a light burning bright before it burns out. If you’ve ever had that experience, you’re in a room and all of a sudden the lightbulb gets really intense and then it burns out. So, you hear us basically burning out.

And there’s a sort of incandescent poetic beauty to all that, and there’s just the sorrow to it because you also realize it’s the last of that moment. In many ways, it was truly the end of that band. I mean, yes, the band has continued, and James [Iha] and Jimmy [Chamberlin] and I have been playing back together again for seven years, and released more records and had a tremendous amount of success of late.

But you can never recapture the innocence of youth or the innocence of the time. When you combine those types of experiences with loss and sorrow and the knowledge of what didn’t happen or what could have happened, then it makes revisiting this time bittersweet.

Q: What do you think “Mellon Collie” means today and how has it been for you to see younger generations continue to be inspired by it?

A: I view that album in particular very much within the realm of a child who grows up in a latchkey situation. It’s very much a Gen X term. Latchkey kids were those whose parents were working a lot or not home, so they grew up by and large unsupervised. So what does a kid who grows up unsupervised do? They watched a lot of television, and then we consumed a lot of sugar and got up to a lot of delinquent-type things.

So I think the album is very representative of that experience and I think why it continues to resonate for subsequent generations is, it’s very dissociative. Back in the ’90s, the mainstream culture, including the L.A. Times and the New York Times, they really struggled with, “Where’s this all coming from?” Now you are living in a world that is constantly dissociative thanks to social media.

The thing that’s surprising, I’m basing it on personal conversations I’ve had with tons of musicians through the years, is that our album gave some musicians the permission to pursue a wider artistic vision. Because “Mellon Collie” is so wide. It has so much breadth. So what I’ve heard from other artists is, “Wow, when I heard that album, I thought, I can do this too, but in my own way.” And that to me is like, that’s a penultimate compliment from another musician. It’s really humbling.

The greatest thrill now is seeing that young people really do connect with the record. And they connect with songs that are different from the previous generations, which is even cooler. They seem to like the weirder stuff on it rather than the ... let’s call it, the classic rock alternative stuff.

Q: That’s a cool way of looking at it. Like the previous generation probably was really obsessed with “Bullet with Butterfly Wings,” and maybe newer listeners aren’t as focused on that song specifically. In that song, it’s interesting that you say, “Can you fake it for just one more show?” Or this feeling of putting on a performance and feeling that you have to fake it as an artist. Is that something that still resonates with you?

A: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Because you work so hard to be on that stage and then, as Roger Waters so aptly describes in “The Wall,” you find yourself having a surrealist experience on that same stage. You put yourself through hell to get there and then one day you’re standing there and you’re like, what am I doing here?

I’ve had similar moments where I’m standing on stage and you feel like you’re tripping on drugs, but you’re totally sober. Because the thing that you love inverts on you. When I was a kid, I thought being on TV was a peak thing. But then I was there, about to perform on TV, and there were all these things going on, like you’re tired, or you’re being sued or your bandmate doesn’t like the deli tray. And I just thought, what am I doing here? I felt like I was living in “Spinal Tap.” This is supposed to be fun. This is supposed to be glamorous. This is supposed to be a thousand other things that you put on the rock-star checklist and you find yourself saying, I don’t want to be here.

If you turn to your friends or your family and say, “I’m really struggling with how I’m supposed to process the information that I’m receiving up here,” you’re told you’re ungrateful or you’re out of your mind or you really need to check your ego. I reached a point where it was like, no, I don’t have the skill set to survive punishing my mind, body, spirit five to six nights a week in front of strangers singing songs that are very personal to me and I hear the cheering and I see the flash bulbs popping, but I’m so numb that I can’t feel what’s happening. So in a lot of ways, that song and the themes from the album are still real.

Q: You’ve said in the “Mellon Collie” sessions, you guys were working on 50 songs at once, that you’re working for six hours a day, just really intense in the studio. What are your thoughts as you think back to that? Were there any memories that really arise for you?

A: Despite our public persona of being dysfunctional and brawling, we were quite quiet in the rehearsal space. We almost never had guests and 97% of the time, it was just the four of us in a room working.

So, the real memory for me is just day after day after day of trying tons and tons of different ideas, and it started to wind itself into a story through those 60-plus songs, many of which came out in those few years. It was our best period of musical alignment and I think you can hear that. We worked very hard and very peacefully together for eight months to put all that together.

We had just come off a tour, “Siamese Dream,” which was a 14-month tour, and we went in the studio for eight months, made the “Mellon Collie” record, and we immediately went back on tour. And that tour was 22 months long. So when you ask my memory from that time, it’s like, can you describe the blur? It was a really beautiful blur, you know?

Q: You said something really interesting earlier about “Tonight, Tonight” coming to you with the sound of an orchestra. Talk about what it was like to see that song and this album come to life as an opera with Chicago Lyric.

A: The idea that I would even not only write something on the piano, and now, a full orchestra is playing that song here in Chicago with the lyrics I wrote ... is totally mind-blowing. The first time I heard it with an orchestra, I started to cry, because I thought, this is so crazy. This song that I used to teach myself how to play the piano was now being played by some of the greatest musicians in the world in this beautiful opera hall. I can’t explain to you the strangeness of that journey.

I was made fun of [for using classical instruments in ’90s rock music]. It was seen as too precocious or too artsy or too, I don’t know, overly grand. And now, if you look at alternative music, I mean, there’s been an absolute explosion of people using unconventional instrumentation within the breath of alternative music, as it should be. So it makes me laugh now that there was a time where somehow that was pseudo-controversial.

Q: Coming to my last question for you, how did this album impact your life 30 years later and impact your artistry?

A: After putting out something like this, artistically it was a triumph. But then publicly it became surreal. We hit a level where people were following you through malls and we were on MTV. It’s not like we had not tasted success, but this was this other stratospheric aspect of success. And something about that album just kind of blew everything wide open.

Family relationships, personal relationships, business relationships, everything just kind of went sideways. I remember thinking nothing was quite the same after that album. Which is true, but it’s not true the way you think it is.

The album has never left my life and is never far away from the conversation. It was never like I put it down and left it behind. Other people won’t let me forget and that’s a good thing because the value holds, and I’ll never forget about it.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments