From legendary musician Fela Kuti to 'witches,' these graphic novels are must-reads

Published in Entertainment News

Four new books offer readers a rich volume of cartoons with “Far Side”-level wit, but also go deep on a diverse array of real-life figures, from Afrobeat megastar Fela to the infamous Mitford sisters and the legacy of the Salem “witch” trials.

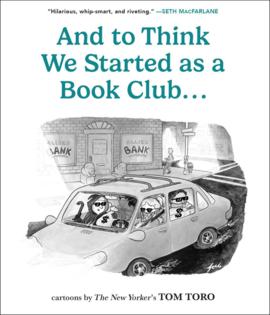

And to Think We Started as a Book Club…

By: Tom Toro.

Publisher: Andrews McMeel, 208 pages.

We know what we’re in for with New Yorker cartoons. Sarcastic, anthropomorphized animals, jammed-up panels of Roz Chast anxiety, couples lobbing witticisms of a half-century ago, updated by references to Instagram. The good news about Toro’s collection of cartoons from the magazine, “And to Think We Started as a Book Club…," is that it’s not all bog-standard fare. The maybe-good, maybe-bad news (depending on your appetite for this kind of thing) is that it also doesn’t stray too far from what subscribers expect.

Chopped into seven arbitrary “Book of…” chapters (“Life,” “Love,” and so forth), the 200 or so one-panel cartoons here cover fifteen years of Toro’s work. Some have a mordant, Gary Larson quality, like the duck saying to another duck while flying unawares over an aiming hunter, “It’s that time of year when guys randomly explode.” Others mine the expected vein of relationship humor with deft wordplay (“The moment we met, I knew he was the man I’d settle for.”) Standouts joust with darkness, such as the man telling a fireside tale to children in a post-apocalyptic landscape (“Yes, the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we created a lot of value for shareholders.”) While few achieve the instant-classic status of the title cartoon (a line of dialogue spoken by one of several bank robbers speeding away from a heist), the book is nevertheless hard to put down.

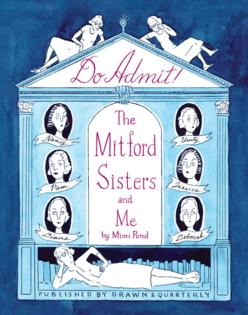

Do Admit! The Mitford Sisters and Me

By: Mimi Pond.

Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly, 452 pages.

The best memoirs sometimes involve the author as much as her subject. Pond’s dense but delectable “Do Admit!” is ostensibly about the infamous Mitford sisters, six aristocratic Brits raised in a strict Victorian manner who then attracted decades of scandal and wonder. But Pond’s narrative is just as much about her yearning, as a child in 1970s’ Southern California, for the sophistication and glamor the Mitfords represented.

Across hundreds of vibrantly drawn and spryly comedic pages, Pond tries to condense the Mitford saga as best she can. Growing up in a grand home “in the exact middle of nowhere” in the early 20th century, the sisters split off like sparks from a fire. Nancy became a comic novelist who mocked her own class (“The Pursuit of Love”), Jessica a Communist and journalist (“The American Way of Death”) who feels closest to Pond’s heart, while Deborah (aka “Debo;” they all had nicknames, of course) married a duke and Pamela was the animal-loving, country-dwelling “quiet one.”

Others took darker paths, like Diana’s and Unity’s fiercely pro-Nazi beliefs. Each was a magnet for attention, whether as scandal-sheet debutantes or political firebrands, and most had razor wits that they occasionally turned on each other. It’s a testament to Pond’s own felicity of style that the Mitfords’ jam-packed lives are rendered here not as a mess of gossip and incident but a vigorous, finely wrought narrative in which one family manages to encapsulate many of the great struggles of the century.

Fela: Music is the Weapon

By: Jibola Fagbamiye, Conor McCreery.

Publisher: Amistad, 384 pages.

The kind of musician whose infectious work turns fans into proselytizers, Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer and revolutionary flamethrower Fela Kuti has no real analog in American music. How could he? Even Prince, whose restless creativity and capacity for complex groove generation has some touchpoints with Fela, never fought the federal government or formed his own country. Fagbamiye and McCreery’s exuberantly drawn graphic biography shows how the seemingly unstoppable Fela was as much charismatic polymath and symbol of change as he was a musician. Unfortunately for this raw, jam-packed book, narrated by a gleefully obscene Fela (who doesn’t mind stretching the truth when it helps the story), the former is far more vividly presented than the latter.

Born in 1938 to an activist mother and preacher father, Fela picked up music early. By the late 1950s, he was getting a jazz education. He jammed in London clubs before returning to Lagos where, in the 1960s, all anybody wanted to hear was James Brown covers. The polyrhythmic funk he brought to jazz did better in California, where he met a Black Panther who introduced him to writings that informed his radicalism back in Nigeria. Aspects of Fela’s burgeoning popularity could be off-putting to outsiders — his 28 wives and sexist attitudes, in particular. But the complex inventiveness of his music (which readers will have to hear themselves, since it’s challenging for Fagbamiye and McCreery to put it across graphically) and the bold stances he took against an oppressive, murderous government are like a template for creative activism.

More Weight: A Salem Story

By: Ben Wickey.

Publisher: Top Shelf Productions, 532 pages.

The term “witch hunt” is so commonly used it verges on losing all meaning. Wickey’s dense, haunting graphic novel about the 1692 Salem massacre of 20 innocents is an illuminating reminder of the theocratic terror that casts a shadow, centuries later. Using crabbed lines, spooky shadowing and harrowed expressions, Wickey employs a thrillingly big canvas to tell his story. He jumps from an episodic retelling of the trials to an imaginary 1860s dialogue between two ghostly writers whose works touched on Salem: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who wrote a play about Giles Corey, the cantankerous farmer whose rumored last words at execution give the book its title; and Nathaniel Hawthorne, who changed the spelling of his name to avoid connection with trial judge John Hathorne.

Wickey, an animator and cartoonist who grew up near Salem and is related to one of the last people executed, invests his narrative with an unusual and welcome depth of feeling. The episode’s mob violence, the absurdity of death sentences being passed due to “spectral evidence” given by hysterical children and the ease with which everyday resentments and fears were turned into tragic morality plays are rendered with a cool fury that stays rooted in history. Wickey closes the book with a jolting examination of Salem’s touristy “exploitation and commercialism” and the irony of the massacre being used to celebrate witchcraft, even though as the author reminds us, “there were no witches in 1692.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments