Arsenic in books? Exhibit shows that some pages can kill

Published in Lifestyles

BALTIMORE -- A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. But who knew that books could kill?

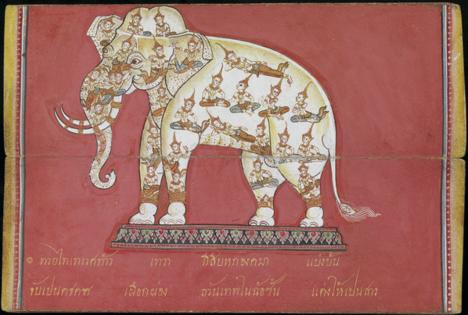

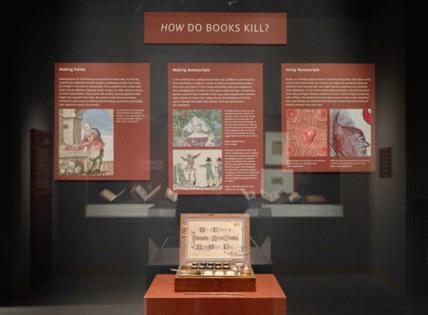

That’s the premise of an exhibit at Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum that looks at four toxic pigments used for millennia and around the world to illustrate and bind books: mercury, arsenic, lead and the bright-yellow mineral known as “orpiment.” The chance to see the show, which has been open since December, is winding down, as the exhibit wraps Aug. 3.

These metals and minerals produced jewel-like, dazzling colors — a brilliant green that could outshine emeralds, a reddish orange found in sunsets, a yellow so bright it could pass for gold. The lead is the basis for a color known a “lead white,” an opaque, silky pigment that retains its bright hue for literally centuries. Some of these tints were so seductive and beguiling that death could be seen as almost worth the risk. They remained in circulation for hundreds of years after their dangerousness was documented.

For instance, the color “Paris green” — introduced in 1814 and a favorite of such artists as Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh and Mary Cassatt — contains arsenic.

”It was completely different from all the other green pigments, and people went crazy for it,” said Annette Ortiz Miranda, a conservation scientist for the museum who co-curated the exhibit with Walters staffers Lynley Anne Herbert and Abigail Quandt. “It was used in everything: clothes, wallpaper, book binding, pigment and makeup. By the mid-1800s, they knew it was making people ill. But it wasn’t fully banned until the 1960s.”

Although poisonous minerals have been found in works dating back thousands of years to ancient Egypt, Ortiz Miranda noted that harmful chemicals aren’t only found in artworks created in the past. Some paintings made today could also be accompanied by a warning label depicting a skull and crossbones. For instance, the spray paint used for graffiti contains volatile organic compounds and heavy metals that can cause respiratory problems and neurological damage if inhaled or absorbed through the skin.

“That is why you see graffiti artists wearing masks with filters,” Ortiz Miranda said. “They are protecting themselves. They still use toxic chemicals but in a more responsible way.”

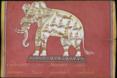

The exhibit consists of two dozen objects in the Walters collection ranging from the 11th through the 20th centuries: books, manuscripts, leaves of parchment and minerals. There is a section on the methods ancient people used to protect their precious volumes from the critters that munched on including real-life bookworms (actually, book lice).

Some remedies worked fairly well, such as leaves from the citronella plant, used today to repel mosquitoes. Others were perhaps less effective, including an inscription intended to summon the protective plant’s “spirit” but that contained no actual citronella.

“It is notable that this manuscript has no traces of insect damage,” reads the wall text accompanying a 16th century illustrated Islamic book by the Persian poet Sa’di. “Perhaps those bookworms really could read!”

The inspiration for the exhibit began in 2016, when the Walters acquired a small missal created more than a century earlier by Clothilde Coulaux, a young Frenchwoman living in German-occupied Alsace. The 174-page book of illustrations is tiny — not quite 5 inches tall and 3.5 inches wide. But it was surprisingly heavy.

“The parchment used in the 20th century was of a much lower quality than parchment from the medieval era,” Ortiz Miranda said. “We examined the book and found that every page was coated on both sides with lead white to give it a nice smooth surface that made it easier for her to illustrate.”

Then, six years later, the Walters acquired a 1788 prayer book from either Germany or America. It included evidence of poisonous chemicals — in this case, lead arsenate, which was used as a pesticide to preserve the book, if not the humans who owned it.

And just like that, the Walters had the nucleus of its current exhibit.

This show also delves into the human stories of the people who interacted with the books: the men and women who created these volumes or later used them. Most deadly chemicals are stealth killers, accumulating in the body invisibly and gradually.

A wall text accompanying the exhibit notes that “books were made to be touched and handled,” and the owners’ interaction with sacred texts in particular could be intense.

For example, a 15th century Gospel book from Turkey is opened to a page showing an illustration of Jesus Christ beset by his enemies — Roman centurions and the disciples who betrayed him.

As was customary at the time, indignant readers expressed their anger at Christ’s assailants by using their fingernails to scratch off the heads and faces in the illustrations. As they did, they unknowingly rubbed cinnabar, an extremely toxic mineral with a high mercury content onto their hands.

In addition, a 15th century Flemish book of hours shows signs that the mercury-laced reddish paint meant to depict Christ’s wounds on the cross has worn away after the page was kissed repeatedly by its devout owner.

Perhaps even more at risk were the monks and nuns who created these exquisitely beautiful illuminated manuscripts. It was work that required long hours at a workbench, heads bent over wet pages, giving new meaning to the phrase “burying their heads in a book.”

Making matters worse, it wasn’t unusual for illustrators to use their lips and tongue to shape the ends of the ink-stained brushes into the sharp points that gave these paintings their elaborate details.

“People were exposed to dangers that they weren’t even aware of,” Ortiz Miranda said.

The Walters exhibit doesn’t contain evidence of any fatalities that can be conclusively attributed to the use of poisonous chemicals — including the museum staff members who put this show together.

“No curators, conservators, or art handlers were harmed in the making of this exhibition,” the wall text says.

But a study published in the August 2008 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science analyzed the bones of medieval monks buried in six cemeteries in Denmark. Researchers found high concentrations of mercury and concluded that they likely came from the red ink used to write script in the incunabula, or religious books printed in Europe between 1450 and 1501.

Ortiz Miranda’s favorite manuscripts on view in the exhibit, the confession books created by deaf children in the 19th century are almost unbearably poignant. Because these youngsters couldn’t confess their sins verbally and be absolved, they painted pictures of their youthful misdeeds and showed them to their priests.

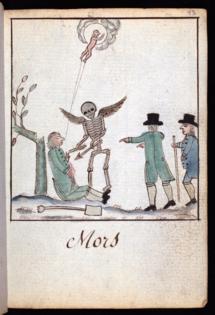

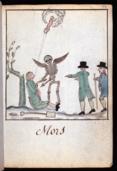

One 19th century drawing by a preteen Flemish boy named Carel shows him sitting under a broken and dying tree, beset by a winged skeleton thrusting two arrows at his chest. Two grown men stand nearby, and one is pointing directly at the youth. The illustration is titled “Mors” or “death.”

The exhibit curators wrote that the image was possibly intended to encourage Carel to behave by reminding him of his mortality. But death might have been hovering even closer than the boy could have guessed. The tree, the boy’s coat and the coat worn by the pointing man are all painted a deadly Paris green.

“He could not have known,” the wall text concludes, “that he was taking his life in his hands.”

____

If you go

“If Books Could Kill” runs through Aug. 3 at the Walters Art Museum, 600 N. Charles St. Free. For details, call 410-547-9000 or visit thewalters.org.

____

©2025 The Baltimore Sun. Visit at baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments