Mary Ellen Klas: The GOP's Medicaid cuts have a very convenient timeline

Published in Op Eds

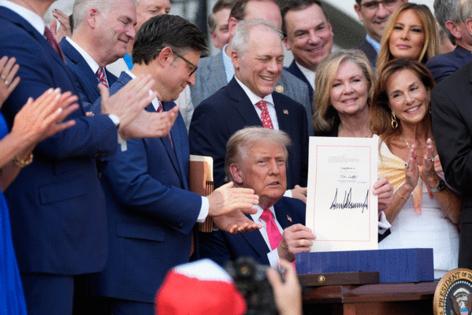

When President Donald Trump signed his tax bill into law, he acknowledged it included deep spending cuts but suggested people “won’t even notice it.”

“The people are happy, they’re happy,” he added.

Judging from the reaction of Republican lawmakers, including those the swing states that will decide the partisan makeup of the House and Senate, Trump is probably going to be right.

Control of the Senate in 2026 could hinge on races in two southern swing states: Georgia and North Carolina. They each have one of the most competitive Senate races in the country. North Carolina has an open seat because of the retirement of Republican Thom Tillis. And Georgia has a competitive seat because Democrat Jon Ossoff narrowly won it in 2020.

Unfortunately for Republicans, the $3.8 trillion tax-and-spending bill they just passed will hit voters in both states hard. The Medicaid cuts are expected to leave 660,000 North Carolinians without health insurance and close or reduce services at five rural hospitals. In Georgia, 310,000 could lose health insurance and four hospitals are expected to close. The law’s slashing of Biden-era clean-energy investments also is expected to kill as many as 42,000 Georgia jobs.

But the GOP designed their One Big Beautiful Bill Act so that the impact of its safety-net cuts won’t be felt before the 2026 elections. Although the tax cuts for the wealthy take effect in 2025 and 2026, the deep cuts to safety net programs that slash $1 trillion from Medicaid over the next decade won’t start causing pain until 2027. This delay is no accident.

Beginning in 2027, the 40 states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act will have to start ratcheting down the incentives they use to prod hospitals and health-care facilities to accept public insurance.

Also in 2027, the new work requirements and increased paperwork to enroll in Medicaid will take effect. Unless states invest millions of dollars in the administrative infrastructure needed to monitor compliance, researchers estimate that 11.8 million people are expected to be kicked off their health insurance over 10 years.

The law also restricts state-directed payments to hospitals, nursing facilities and other providers that depend upon Medicaid. Rural areas are expected to be hardest hit, according to KFF, a non-profit health policy organization. North Carolina will lose about $7.5 billion in rural health care spending over 10 years, second only to Kentucky, while Georgia, which did not expand Medicaid, would lose $2.3 billion. These cuts don’t take effect until 2028.

Republicans also delayed the impact of cuts to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, known as SNAP or food stamps, but only for nine states — including politically important Georgia and Alaska. Democrats claim Senate Republicans used the carve-out to win the vote of Alaska’s Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski.

And the delays to the cuts are only part of the GOP’s midterms strategy.

Republicans are counting on three other things to immunize them from voter backlash for these and other cuts in the bill, explained Eric Heberlig, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. They assume that low-information voters in pivotal swing states won’t know the negative impacts and hidden costs the budget bill could have on their lives. They believe their supporters prefer that they demonstrate fealty to Trump over fighting for constituent needs. And evidence shows that low-income people are less likely to vote in the midterm elections than those with higher incomes.

“It used to be that you represented the particular needs of your constituents and were proud to vote against the party when you were fighting for the needs of your community, but now it’s the complete opposite,” he added. “Even party activists want you to vote based on national ideology and the party line, rather than stick up for local needs.”

Tillis’ exit is the result of the political brinkmanship Republicans are playing. He was already one of the most vulnerable Republicans in the Senate. If Trump were concerned about retaining the seat, he would have given Tillis the space to criticize the budget bill. Senate Republicans could have given him a deal, like the one Murkowski took in exchange for her reluctant vote for the bill.

But Trump didn’t deal. He just demanded loyalty. So Tillis called it quits and voted against the bill, increasing the odds that Democrats will flip his seat next year.

Democrats obviously see opportunity here. They point to 2018, when Democrats used Trump’s failed repeal of Obamacare to defeat 36 House Republicans and regain control of the chamber.

But 2018 seems like a lifetime away. Then, the governors of the 19 Republican-led states that expanded Medicaid were instrumental in halting Trump’s first attempt to undermine the Affordable Care Act. They are now silent, even though the measure is going to blow billion-dollar holes in their budgets.

The average voter won’t piece that together. They like Medicaid work requirements in theory, but also aren’t likely to understand the hidden costs of the cuts — that their health care costs will likely rise because Medicaid payments to hospitals are being reduced, because millions of Americans will be losing health insurance, and because hospitals’ uncompensated care costs will soar.

“In many poor rural districts, voters know that Republicans have never been interested in supporting social welfare programs and yet they get reelected consistently anyway,” Heberlig told me. “So yeah, they’re willing to vote for representatives who arguably are doing them economic harm.”

Republicans have already gamed this out. But the question is whether they are going to have to reckon with what they’ve done, and whether it will matter before the 2026 midterms.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mary Ellen Klas is a politics and policy columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former capital bureau chief for the Miami Herald, she has covered politics and government for more than three decades.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments