Is a united European voice possible in the age of Trump, Putin and far-right politics? Germany’s new leader intends to find out

Published in Political News

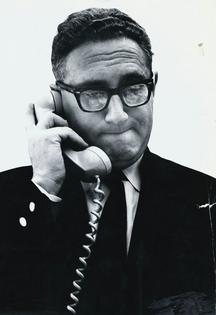

“Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?”

The question was famously attributed to former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and refers to the historical inability of the political entity of Europe to coordinate on a united front in the global arena.

And despite decades of integration under the European Union, who speaks for Europe – or what the bloc desires to be – is perhaps less clear now than at any point in recent years. Internal cleavages over immigration, right-wing nationalism, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Donald Trump’s return to the White House all challenge the notion of what Europe is and should stand for.

Friedrich Merz, the expected next chancellor of Germany, offered one continental vision shortly after his conservative party triumphed in the country’s national elections. “My absolute priority will be to strengthen Europe as quickly as possible so that, step by step, we can really achieve independence from the USA,” he said.

Merz’s apparent desire for a stronger German role could portend a balance shift back to Germany’s preeminent place in the EU, a position it has pulled back from in recent years. But it remains an open question as to what extent Europe can be unified given the continent’s political landmines – or even what kind of Europe it would be.

A German leader has, in living memory, succeeded in providing something approaching a singular European voice that the White House could deal with. Europe was long synonymous with Angela Merkel, Germany’s long-lasting – and only female – chancellor, who was known by affectionate nicknames like “Mutti Merkel,” or “Mommy Merkel,” and, during Trump’s first time in office, was even referred to by some as the de facto leader of the free world.

Her legacy – Merkel served from 2005 to 2021 – was defined in part by strong commitments to clean energy, welcoming hundreds of thousands of refugees during the 2015 European migrant crisis and championing German leadership of the European Union. In the process, she became something of “Europe’s engine.”

Merkel collaborated especially well with France’s Emmanuel Macron, a passionate fellow Europeanist, communicating a vision of a united Europe and its core values to the rest of the world. Dubbed “Merkron” by commentators, the pair were seen as the EU’s power couple.

Meanwhile, former U.S. President Barack Obama often described Merkel as his closest ally, praising her humanitarian vision of refugee politics and even decorating her with the Medal of Freedom, the highest honor that the U.S. can award to a foreign national.

Merkel was visionary, too, especially regarding the former superpowers of the Cold War and their controversial leaders. A child of East Germany, she never trusted Russia’s Vladimir Putin. She also experienced great difficulties collaborating with Trump during his first presidency. Somewhat anticipating Merz’s recent comments, Merkel in 2017 warned that neither Germany nor the EU could rely on the U.S. the way they used to, urging her fellow Europeans to take their fate and their interests in their own hands.

But in some ways Merkel was more popular abroad than at home.

The so-called “German question” – or the inability of the Germans to unify as a nation in its leadership and “Leitkultur,” or “guiding culture” – has been tormenting the country since the 19th century and gained renewed relevance during the years of German reunification following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Years on from the so-called “Miracle of Merkel,” Germany’s increasing internal political divisions – especially pronounced between the country’s West and East – mirror the broader divisions facing the EU at large, including over who should claim the mantle of political leadership and around what vision.

To regain the gravitas within Europe it had under Merkel, Germany now would need a similar kind of strong and visionary program that resonates with the continent. The country’s political, economic and social challenges in 2025 demand clear national leadership, something that in my opinion neither the unemotional and uncharismatic outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz nor the opposition right-wing leader and soon-to-be successor Merz has demonstrated in public over the past couple of years.

Although Merkel and Merz represent the same political party, the CDU, their visions for Germany and the EU are strikingly different. A wealthy former business lawyer, Merz’s signature book, “Dare More Capitalism,” is a blueprint for a policy agenda that prioritizes reduction of government intervention, less bureaucracy, lower taxes and pro-market reforms. Merz also wants to strengthen German borders with restrictionist immigration politics, a reflection of how the country has moved far to the right on the issue amid the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), with whom Merz has at times flirted.

Yet in Merz’s relatively different agenda, he similarly advocates for both Europe and NATO, and wishes to refashion Germany into the powerhouse it was in the Merkel years and make it again the envy of Europe.

Given the current “America First” attitude of the Trump administration and the rise of far-right populism across the EU and the world, it is thought-provoking – some would say alarming – that Trump declared the results of an election that saw strong gains for the far right – propelling it into second place – as a “great day for Germany.”

Whether it is great for Europe depends on what vision of the continent one has in mind. Merz, although more right wing than Merkel, nonetheless has advocated for a strong Europe, led by Germany, that could promote a Europe independent of U.S. influence, appearing to follow in the steps of former French President Charles de Gaulle, who sought to cleave Europe from American dominance.

During his recent speech at the Munich Security Conference, U.S. Vice President JD Vance warned of a European “threat from within,” disparaging continental governments for their retreat from “fundamental values, values shared with the United States of America,” while defending far-right populism and policies on the continent. Elon Musk subsequently posted on his social platform X: “Make Europe Great Again! MEGA, MEGA, MEGA!”

Despite the bewilderment and dismay expressed by the European leaders at such statements, today’s tormented and divided Europe can hardly claim it is a problem-free environment, nor that many of the continent’s leaders don’t likewise support such politics.

The rise of populism and nationalism across Europe poses a huge problem for what could unceremoniously be described as “Old Europe,” especially now, when it is seemingly drifting apart from its former ally and protector, the United States.

With Russian influence and authoritarian politics growing in Central Europe – especially in Hungary and Slovakia – and ultra-nationalist and far-right ideas likewise strong in Austria, Germany, France and elsewhere, today’s Europe is hardly a unified political, economic and cultural totality.

In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing political chameleonism, combined with her defense and praise of both Musk and Trump, is also a problem for those searching for a Europe unified more toward the political center.

Less than a year ago, France’s Macron, the still-passionate Europeanist, marked a somber note in suggesting: “We must be clear on the fact that our Europe, today, is mortal. … It can die, and that depends entirely on our choices.”

Among other things, what Macron’s warning points to is the unresolved question of what the European bloc desires to be. So long as the answer to that question remains unclear, Kissinger’s question could be rephrased to, “Is there even a Europe to call?”

And, given the Trump administration’s emerging hostility to a host of EU policies, including on the war in Ukraine, foreign aid, regulation and trade, there is a further worrying interpretation for EU leaders, even if there were “a Europe to call”: Would Washington bother picking up the phone?

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager, Colorado State University

Read more:

Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting prioritizes ‘real’ independence from the US − but what does that mean and is it achievable?

Who is Friedrich Merz, the man now most likely to lead Germany? Eight things to know

Will Trump victory make Angela Merkel leader of the free world?

Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments