Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores precedent that only states decide who gets to vote

Published in Political News

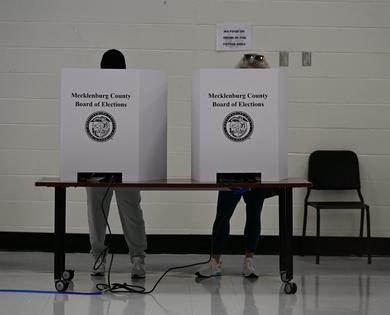

The Republican-led House of Representatives passed on April 10, 2025, the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act – or SAVE Act. The bill would make voting harder for tens of millions of Americans.

The SAVE Act would require anyone registering to vote in federal elections to first “provide documentary proof of U.S. citizenship” in person, like a REAL ID or a passport.

The House already passed an identical bill in July 2024, also along partisan lines, with the GOP largely supporting the legislation. At that time, the Senate killed the bill. With a now GOP-controlled Senate, and a Republican in the White House, the SAVE Act could become law before 2025 ends.

Voting rights experts and advocacy organizations have detailed how the legislation could suppress voting. In part, they say it would particularly create barriers in low-income and minority communities. People in such communities often lack the forms of ID acceptable under the SAVE Act for a variety of reasons, including socioeconomic factors.

As of now, at least 9% of voting-age American citizens – approximately 21 million people – do not have even have driver’s licenses, let alone proof of citizenship. In spite of this, many legislators support the bill as a means of eliminating noncitizen voting in elections.

As a legal scholar who studies, among other things, foreign interference in elections, I find considerations about the potential effects of the SAVE Act important, especially given how rare it is that a noncitizen actually votes in federal elections.

Yet, it is equally crucial to consider a more fundamental question: is the SAVE Act even constitutional?

The SAVE Act would forbid state election officials from registering an individual to vote in federal elections unless this person “provides documentary proof of United States citizenship.”

Acceptable forms of proof for registration would include REAL ID, a U.S. passport or a U.S. military identification card. A regular driver’s license alone would not be enough unless it shows the applicant was born in the U.S., or if it is accompanied with a birth certificate or naturalization certificate.

So, should the SAVE Act become law, if a person turns 18 or moves between states and wishes to register to vote in federal elections in their new home, they would likely be turned away if they do not have any such documents readily available. At best, they could still fill out a registration form, but would need to mail in acceptable proof of citizenship.

For married people with changed last names, among others, questions remain about whether birth certificates could even count as acceptable proof of citizenship for them.

Despite the national conversation the SAVE Act has sparked, it is unclear whether Congress even has the power to enact it. This is the key constitutional question.

The U.S. Constitution imposes no citizenship requirement when it comes to voting. The original text of the Constitution, in fact, said very little about the right to vote. It was not until legislators passed subsequent amendments, starting after the Civil War up through the 1970s, that the Constitution even explicitly prohibited voting laws that discriminate on account of race, sex or age.

Aside from these amendments, the Constitution is largely silent about who gets to vote.

Who, then, gets to decide whether someone is qualified to vote? No matter the election, the answer is always the same – the states.

Indeed, by constitutional design, the states are tasked with setting voter-eligibility requirements – a product of our federalist system. For state and local elections, the 10th Amendment grants states the power to regulate their internal elections as they see fit.

States also get to decide who may vote in federal elections, which include both presidential and congressional elections.

When it comes to presidential elections, for instance, states have – as I have previously written – exclusive power under the Constitution’s Electors Clause to decide how to conduct presidential elections within their borders, including who gets to vote in them.

The states wield similar authority for congressional elections. Namely, according to Article I of the Constitution and the Constitution’s 17th Amendment, if someone can vote in their state’s legislative elections, they are entitled to vote in its congressional elections, too.

Conversely, the Constitution provides Congress zero authority to govern voter-eligibility requirements in federal elections. Indeed, in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling on the Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council case, the court asserted that nothing in the Constitution “lends itself to the view that voting qualifications in federal elections are to be set by Congress.”

The SAVE Act presents a constitutional dilemma. By requiring individuals to show documentary proof of U.S. citizenship to register for federal elections, the SAVE Act is implicitly saying that someone must be a U.S. citizen to vote in federal elections.

In other words, Congress would be instituting a qualification to vote, a power that the Constitution leaves exclusively to the states.

Indeed, while all states currently limit voting rights to citizens, legal noncitizen voting is not without precedent. As multiple scholars have noted, at least 19 states extended voting rights to free male “inhabitants,” including noncitizens, starting from our country’s founding up to and throughout the 19th century.

Today, over 20 municipalities across the country, as well as the District of Columbia, allow permanent noncitizen residents to vote in local elections.

Any state these days could similarly extend the right to vote in state and federal elections to permanent noncitizen residents. This is within their constitutional prerogative. And if this were to happen, there could be a conflict between that state’s voter-eligibility laws and the SAVE Act.

Normally, when state and federal laws conflict, the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause mandates that federal law prevails.

Yet, in this instance, where Congress has no actual authority to implement voter qualifications, the SAVE Act would seem to have no constitutional leg on which to stand.

So, why have 108 U.S. representatives sponsored a bill that likely exceeds Congress’s powers?

Politics, of course, plays some role here. Namely, noncitizen voting is a major concern among Republican politicians and voters. Every SAVE Act cosponsor is Republican, as were all but four of the 220 U.S. representatives who voted to pass it.

When it comes to the constitutionality of the SAVE Act, though, proponents simply assert that Congress is acting within its purview.

Specifically, many proponents have cited the Constitution’s Elections Clause, which gives Congress the power to regulate the “Times, Places and Manner” of congressional elections, as support for that assertion. Sen. Mike Lee, for example, explicitly referenced the Elections Clause when defending the SAVE Act earlier in 2025.

But the Elections Clause only grants Congress authority to regulate election procedures, not voter qualifications. The Supreme Court explicitly stated this in the Inter Tribal Council ruling.

Congress can, for instance, require states to adopt a uniform federal voter registration form, and even include a citizenship question on said form. What it cannot do, however, is implement a non-negotiable mandate that effectively tells the states they can never allow any noncitizen to vote in a federal election.

For now, the SAVE Act is simply legislation. Should the Senate pass it, President Donald Trump will almost assuredly sign it into law, given, among other factors, his March 2025 executive order that says prospective voters need to show proof of citizenship before they register to vote in federal elections. Once that happens, the courts will have to reckon with the SAVE Act’s legitimacy within the country’s constitutional design.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: John J. Martin, University of Virginia

Read more:

What does a state’s secretary of state do? Most run elections, a once-routine job facing increasing scrutiny

Who can defend voting rights? An appeals court ruling sharply limiting lawsuits looks likely to head to the Supreme Court

Voting in unconstitutional districts: US Supreme Court upended decades of precedent in 2022 by allowing voters to vote with gerrymandered maps instead of fixing the congressional districts first

John J. Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments