Sports

/ArcaMax

Paul Sullivan: After getting 'torched' for gaffe, White Sox GM Chris Getz is back to the rebuild business

GLENDALE, Ariz. — What does Luisangel Acuña want Chicago White Sox fans to know about him?

“That I play hard,” Acuña said through an interpreter while sitting at his locker and breaking in his outfield glove.

Simple and to the point.

The new addition to the Sox outfield isn’t going to speak boldly or put expectations on himself. He�...Read more

Former MLB pitcher Dan Serafini sentenced to life in prison for murder of father-in-law

Former Major League Baseball pitcher Dan Serafini was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole on Friday for the 2021 first-degree murder of his father-in-law and attempted murder of his mother-in-law in Lake Tahoe.

Serafini, who pitched for six MLB teams during a 22-year professional career that ended in 2013, killed Gary ...Read more

Red Sox stars avoid major injury scare after frightening outfield collision

NORTH PORT, Fla. — The Red Sox appear to have dodged a huge bullet.

During the bottom of the first inning of Friday’s game against the Atlanta Braves, Red Sox outfielders Roman Anthony and Ceddanne Rafaela collided in left field trying to chase down a fly ball off the bat of Jurickson Profar. The two went down and were immediately attended ...Read more

Ex-MLB pitcher Daniel Serafini gets life sentence for fatal in-law attack

Daniel Serafini, the ex-MLB pitcher convicted of shooting his in-laws in a 2021 murder-burglary at their Homewood, Calif., residence near Lake Tahoe, was committed to life without parole after his sentencing Friday in Placer Superior Court.

Jurors in July convicted Daniel Serafini, 51, of first-degree murder in the death of his father-in-law, ...Read more

Bill Shaikin: Dodgers hype time: How many games will they win in 2026?

PHOENIX — It is never too early for hyperbole.

No major league team has won more than 116 games. The Dodgers had yet to play an exhibition game last spring when former Los Angeles Times columnist Dylan Hernández declared they could win 120.

Not to be outdone, the Dodgers were one week into the season when Bill Plaschke posted a column with ...Read more

Don Mattingly could give Bryce Harper's career a boost with the Phillies. Maybe Harper can reciprocate.

CLEARWATER, Fla. — For 30 minutes Wednesday, on the half-field adjacent to the Phillies’ clubhouse, Larry Bowa flipped baseballs to Bobby Dickerson, who hit one-hoppers and choppers and line drives at Bryce Harper.

Over and over. Again and again.

Ninety feet from Harper, a nine-time Gold Glove-winning first baseman and former captain of ...Read more

Twins reliever Liam Hendriks breaks down his old scouting report, changes as pitcher

FORT MYERS, Fla. — When a reporter approached Liam Hendriks with one of his earliest scouting reports, the veteran relief pitcher offered a prediction about what it would say.

“I’m assuming there is a little bit of short motion with a quick arm, 88-92 mph, with a little bit of arm side run,” Hendriks said. “Good changeup. Breaking ...Read more

David Murphy: Bryce Harper and Scott Boras are right. Here's a wild stat that makes their point.

PHILADELPHIA — No man is an island. Unless that man is Bryce Harper and he has just reached base.

Last season, there wasn’t a lonelier lot in life than to be a Phillies superstar standing on first, second, or third. Only four players in the majors reached base as many times as Harper did and scored fewer runs. The 72 runs he did score were ...Read more

Yankees to retire CC Sabathia's No. 52, unveil plaque in Monument Park in 2026

NEW YORK — The Yankees are adding another number to Monument Park.

The Bombers announced that they will be retiring CC Sabathia‘s No. 52 on Sept. 26 before their game against the Baltimore Orioles, the team announced on Wednesday. The ceremony will include the unveiling of Sabathia’s plaque in Monument Park.

The 2009 World Series ...Read more

Banana Ball gets 'biggest partnership to date' with ESPN and Disney, including a trip to Disneyland

LOS ANGELES — Already well-known for selling out stadiums for baseball-themed spectacles that include choreographed dances, inventive trick plays and outlandish fan interaction, the Savannah Bananas have cemented their synergy with ESPN and Disney+ with a 25-game package in 2026.

Included in the deal will be a "Banana Ball Day" at Disneyland ...Read more

Paul Sullivan: New bidets might help the White Sox flush away the past

PEORIA, Ariz. — The team that bidets together stays together.

Or at least that’s the mantra of the Chicago White Sox after news that the team is introducing bidets in the clubhouse at the request of Japanese slugger Munetaka Murakami.

The jokes write themselves when it comes to the subject of eco-friendly hygiene, but the Sox are using the...Read more

Matt Calkins: Why the next year will be key for future of Major League Baseball

SEATTLE — It's harder to keep a stride in your step when you're feeling a pebble in your shoe.

You could say this about MLB's elite young players, just as you can their most ardent fans.

Because as stable as the sport seems to be right now — with the ungodly contract sizes and last year's exhilarating postseason — there is a looming ...Read more

Tom Krasovic: Former manager Bud Black is again a piece of Padres' 'puzzle'

PEORIA, Ariz. — When the Colorado Rockies fired longtime manager Bud Black in May, the San Diego resident could’ve opted to wind down a professional baseball career he began in 1979 as a Seattle Mariners draftee out of San Diego State.

Not going to happen, I thought.

As Padres manager, Black never seemed to wear down over eight-plus ...Read more

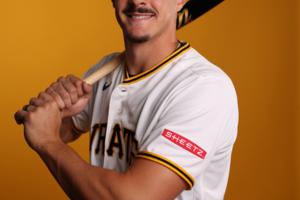

Top Pirates prospect Konnor Griffin steals show with two home runs against Red Sox

FORT MYERS, Fla. — Konnor Griffin could only stare as a man wearing a Paul Skenes shirsey gamely thought he could catch the baseball after Griffin’s first home run of spring training cleared the Green Monster-like structure in left field at JetBlue Park.

Two innings later, the sport’s prospect did something even more impressive, crushing ...Read more

SoCal product Pete Crow-Armstrong disses Dodgers fans with a curious comment

LOS ANGELES — What's not to love about Pete Crow-Armstrong? The young, talented Chicago Cubs center fielder is somehow simultaneously super cool and fiery. Nicknamed simply PCA, he should be an entertaining and accomplished player to watch for many years.

And he's Southern California born and bred, the product of esteemed diamond factory ...Read more

John Romano: Who needs a star closer when the Rays have a bevy of bullpen arms?

PORT CHARLOTTE, Fla. — The closer is a solitary figure, walking in from the bullpen to a banging beat and thunderous applause.

Hitters fear him, and managers depend on him. The very best among them have iconic and, often, edgy music to announce their arrival.

For Mariano Rivera, it was “Enter Sandman.” Trevor Hoffman had “Hells Bells.�...Read more

Tigers' Tarik Skubal confirms he will be one and done for Team USA next month

LAKELAND, Fla. — Tarik Skubal might be serving two masters in the early part of spring, but there is no confusion about his priority.

“I am trying to do both things,” he said. “I am going to pitch for Team USA (in the World Baseball Classic), but also I understand I really need to be here with these guys and get ready for the season.

�...Read more

Paul Sullivan: Who's in right, and other daunting questions for Cubs at spring training

MESA, Ariz. — Chicago Cubs manager Craig Counsell doesn’t have a ton of roster decisions to make this spring.

His starting lineup and rotation are mostly the same. Daniel Palencia returns as the closer, and most of the other bullpen pieces were signed over the offseason.

“That changes,” Counsell said Saturday morning at Sloan Park, ...Read more

Jason Mackey: Marcell Ozuna's healthy hip, immediate clubhouse impact have been hard to ignore

BRADENTON, Fla. — The boisterous discussion among several Latin American Pittsburgh Pirates players had ended. Oneil Cruz, one of the last stragglers, ducked into the athletic trainer’s office. Left alone at his locker inside the home clubhouse at LECOM Park was Marcell Ozuna.

Ozuna’s days here have been busy — and Sunday was no ...Read more

Sewage issues at Steinbrenner Field alter Yankees' practice plans

TAMPA, Fla. – Pungent sewage had the New York Yankees flowing across the street on Sunday morning, as the drainage issues that flooded parts of George M. Steinbrenner Field the previous day forced the Bombers to hold pregame workouts at their Himes player development complex before hosting the New York Mets.

The Sunday exhibition game took ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Don Mattingly could give Bryce Harper's career a boost with the Phillies. Maybe Harper can reciprocate.

- Red Sox stars avoid major injury scare after frightening outfield collision

- Bill Shaikin: Dodgers hype time: How many games will they win in 2026?

- Paul Sullivan: After getting 'torched' for gaffe, White Sox GM Chris Getz is back to the rebuild business

- Ex-MLB pitcher Daniel Serafini gets life sentence for fatal in-law attack