Drum circle lives on after tense police moment

Published in News & Features

TREASURE ISLAND, Fla. – A few hours before sunset, a circle of people begins taking shape around a stick spiked into the sand. It’s a fringe gathering on the fringe of the state, just before the endless-seeming Gulf.

Close to 400 people congregate there behind the public parking lot, “spontaneously” for the purposes of not needing a city permit, though this gathering has somehow happened every Sunday for decades.

There are tourists, curious beach-walkers and locals who wanted their out-of-town visitors to see something memorable. Then there’s the large core of regulars, drawn week after week to the place they call church and the people they call family.

Most importantly at the Treasure Island drum circle, there are drums, big like trash cans, small like pie pans, sideways across laps and strapped over shoulders. All slapped, pounded and thumped with nothing less than total enthusiasm and varying degrees of technical skill.

Some are playing buckets, pots, pans, a xylophone, a saxophone, a textured metal necktie scraped like a washboard. Some are howling like wolves.

The drumbeat grows massive, changes and then dies down to almost nothing. The drummers find each other by instinct, clumsily at first, and then magically, suddenly, they are in unison, the rhythm roaring again.

“It’s almost like when birds fly in the air and get synchronized,” said Desiree Garcia, a Hillsborough County teacher and one of the core drummers.

Those who aren’t drumming dance or leap like they’re doing karate. A man with a third eye, a googly one stuck to his forehead, offers stickers. A woman kneels in front of the stick and rolls her head around on her neck. A toddler builds a sandcastle.

A hint of skunky cannabis blows by, but more faintly than at circles past.

Three Treasure Island Police officers sit in SUVs watching, a reminder that three months ago it seemed like this decades-long tradition was set to be shut down.

_____

In May, Treasure Island police chief John Barkley called upon the city to guide his department in dealing with the drum circle, which he described as a serious problem.

At a city commission meeting, he said the circle drew people who disregarded ordinances against smoking, bringing dogs onto the beach and selling things without a permit.

“I’ve seen this grow,” he said. “The incidents that I’ve seen since I’ve been chief include and are definitely not limited to sexual assault, rampant drug use, Marchman acts — which is when somebody gets too drunk that they cannot take care of themselves or are a danger for themselves or others.” There aren’t enough officers in tiny Treasure Island to safely enter the circle to enforce the law, he said.

Capt. Dan Savarese talked about fights, narcotics, “domestics” and child neglect cases. At one point, he said, the department brought in outside agencies to deal with a gang problem.

Both men spoke of an incident in which an officer making an arrest was punched in the head by another attendee. That officer, they said, was forced to medically retire due to his injuries. “In my opinion, the drum circle should have stopped there,” Barkley said.

A well-known beach cleanup volunteer who’d planned to lobby the chief in the circle’s defense had changed her mind after visiting, Barkley said, telling him she saw people “having relations” in the dunes.

“A lot of times when we’ve made arrests, the people are screaming, you can’t tell us what to do on the beach,” Savarese said. So we’re asking for direction. … We can absolutely come up with a plan and take care of the situation.”

In the audience, Enna Salveter was reeling. The 28-year-old pet nutritionist had first visited the circle with a friend three years earlier. The sense of community she found blew her mind. What she was hearing didn’t sound like the circle she knew.

Sure, things happened on the beach sometimes, whether they were part of the circle or not, especially the smoking and dogs, but this sounded like utter chaos. Like something to be scared of.

It also sounded like the circle would soon be over.

“My opinion is you do what you gotta do to disperse it,” said one commissioner, who found it appalling that the gathering was advertised on the Visit St. Pete-Clearwater site. “I agree,” said another. “It sounds like you have the full support of the commission to go forth with your plan,” a third member told the chief.

“We’re all,” the mayor added, “saying the same thing.”

Maybe the drum circle could continue, they said, if organizers got a permit and insurance and paid for police security like any other event. That would require someone stepping up as the circle’s owner and leader, which no one actually expected to happen.

When the floor opened, Salveter nervously and tearfully read the words she’d written on her phone.

“I found a home, family, loving community and my form of church,” she said. “I’ve met incredible people from around the world who have come to Treasure Island specifically to come and experience the love and the light that circle provides.”

She asked the police to simply tell her how she could help save the thing she loved. Still, she figured that was that.

_____

A circle has no beginning and no end, but Treasure Island drum circle attendees often say theirs began about 40 years ago.

It actually started in 2001, when Christine Marie Loving, an energy healer who needed a project for a leadership course she was taking, teamed with a belly dancer named Johanna Zenobia Taylor. They gathered dancers and a band and put up fliers. Loving wanted people to “be fully self-expressed, in their authenticity and in their essence, without drugs and alcohol.” They took inspiration from a circle on Siesta Key.

Drumming had been a thing in American counterculture hotbeds like Berkeley and Greenwich Village since the 1960s. Communal drum circles formed outside Grateful Dead concerts since at least the early 1980s. But the burgeoning new age movement of the 1990s brought an explosion of hand drums and drumming classes nationwide.

“Drum fever is sweeping the country,” read a 1993 article in the Palm Beach Post. Nuns were using drums to enliven religious retreats. Tech companies held drum circles for corporate team building. Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart was bringing them into nursing homes.

Florida was said to be at the forefront. Circles formed on Ybor City sidewalks where people banged on coffee cans and tortoise shells. Circles formed on beaches in Miami, Nokomis, Sarasota.

The ’90s peak of mainstream new age may have faded, like mall-shopping for rain sticks at Earthbound Trading Co. to a soundtrack of Enya, but the circles persist.

_____

In 1994, Desiree Garcia, the high school reading teacher who drums at Treasure Island, had just come home to Tampa from Alaska. She was pregnant, worried and feeling lost.

Her boyfriend helped her craft a drum and brought her to her first circle on Clearwater Beach. She was hooked. She later took lessons with the Kuumba dance and drum troupe in Tampa.

“It’s just so relaxing, meditative,” she said. “For me, there is a spiritual aspect.”

Attendees said the circle makes Treasure Island special — and draws business to nearby bars and restaurants.

Like with any revelry, there can be issues, Garcia said. She welcomed collaboration with police, she said, even if she felt the complaints misrepresented the circle’s character.

Why Treasure Island’s police chief chose that particular week in May to lay out the problems with the circle remains unclear. He did not respond to requests for an interview.

Police records alone can’t tell the full story, but the past year’s log of calls for service showed mostly minor incidents like parking tickets and unleashed dogs. In April, an officer intervened in a brief, uneventful altercation over bubbles blown in someone’s face.

The most serious recent situation appears to have involved a man arguing with another attendee over accidentally getting sand in their drink. The man was so intoxicated, police said, that they took him to jail under the Marchman Act for safety.

The punch that seriously injured an officer happened eight years ago. The task force to deal with the alleged gang activity came in 2012.

The beach cleanup leader who’d been held up as an opponent told the Tampa Bay Times she actually supports the gathering, as long as people pick up trash. As for the public sex, she clarified that it wasn’t during the circle, it was the morning after.

This summer, Garcia spoke to Chief Barkley and Capt. Savarese, hoping to change their perception. She found them warm and open to her ideas. They mostly wanted someone, she said, to be accountable.

If the circle had any unwritten rule, it was that no one was in charge. Garcia didn’t want to lead, but she could be accountable, she thought.

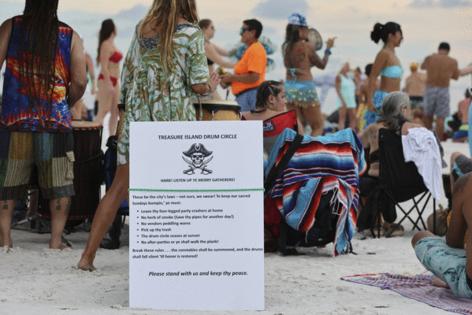

She organized a half-dozen drummers via text, including Salveter. They workshopped wording for guidelines and made signs. They bought a megaphone. They began walking around the circle asking people not to smoke.

“Most people, like 90%, are very cooperative, very cool,” she said. “We say, ‘Hey, the police are going to shut us down if we don’t clean up our act.’”

Salveter, who operates a Facebook page dedicated to the circle, has been diligent about posting reminders about acceptable behavior.

A couple times, when someone got mad, Garcia asked police officers for help, not without discomfort. A couple times, she asked for the drumming to stop until an offender complied.

Some people have bristled at rules intruding upon a gathering dedicated to unbridled expression. In late July, police arrested a 6-foot-8, 300-pound Treasure Island resident named Duncan Small. He is in jail, accused of delivering letters to city commissioners’ homes reading, “We know where you all live, quit f—king with the Drum Circle.”

Crowds have been slightly smaller, perhaps due in part to the police shutting down afterparties that used to draw DJs with portable gear. The circle no longer produces a powerful smell of weed detectable far down the beach.

A spokesperson for the city said cooperation has improved, and there are no plans to shut it down.

Every so many years, these things happen. Drummers on Treasure Island used to play late into the night. About 10 years ago, city leaders looking to crack down on noise entered into informal negotiations with another group of non-leader leaders. After that, the drumming ended at sunset — another compromise to keep the music going.

_____

Sunset is coming. The beat is thumping.

Salveter stands near the water’s edge taking in a glowing cantaloupe sky. She leans her head back, closes her eyes, and says to herself, “There is literally nothing like this moment right now.” She inhales the salt air.

“I don’t have a family, but out here I have three moms,” she said. “I just feel so loved.”

The drumming stops. The crowd applauds the sun dropping under the horizon. The circlers hold hands and chant, om, om, om. They join in a massive group hug.

As one regular walks toward the parking lot, he shouts, “I love you. I love all of y’all, I swear.” Passing one of the police SUVs, he says, “Johnny Law, I love you, too. I swear to God I love you.”

The officer reaches out through the window so they can bump fists and says, “I love you, too.”

©2025 Tampa Bay Times. Visit at tampabay.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments