Fearing ICE, parents make plans for their children's care

Published in News & Features

Brian Todd was watching football on Jan. 11 when federal immigration officers pulled into his driveway, walked over to his neighbor’s house on the east side of St. Paul, detained the adults and left behind two children under 15 years old.

Todd, who has children about the same age, took them in. For days afterward, he tried to track down family from out-of-state. It took nearly a week until a relative picked up the children.

Some immigrant parents, fearful of their children facing similar uncertainty if they were to be arrested, detained or deported, are taking the extreme step of legally transferring parental authority to teachers, co-workers, fellow parishioners and neighbors. The anxiety heightened after reports of federal agents detaining children as young as 5 years old.

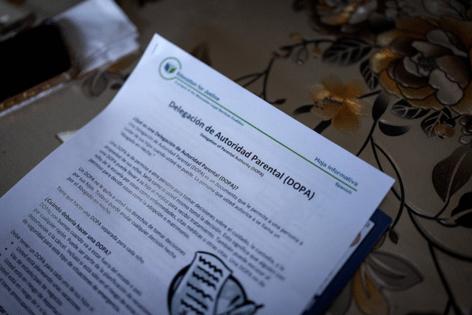

Many immigrants are now signing documents called a Delegation of Parental Authority (DOPA). It legally empowers a third party to make all decisions — educational, medical, travel — for the minor children short of giving them up for adoption.

It’s unknown how many immigrant families have signed such documents, but in the months leading up to the surge immigrant advocacy organizations held group information and notarization events to help families navigate decisions about custody handoffs. Those events mostly have gone underground after waves of immigrants agents arrived in Minnesota in December.

Unidos MN Executive Director Emilia Gonzalez Avalos said it’s a difficult decision that comes with risks, but families are doing it to ensure their children’s basic needs are met.

“We are going to have to deal with a crisis where U.S.-born children are being abandoned ... because the government is taking the people who are responsible for them,” she said.

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin did not answer specific questions about the detainments but said ICE policy is to not separate families.

“Parents are asked if they want to be removed with their children, or if they would like, ICE will place the children with a safe person the parent designates,” Mclaughlin said in a written statement. “This is consistent with past administration’s immigration enforcement.”

McLaughlin also said parents can take control of their departure by self-deporting. For those who take up the offer, the federal government will give them $2,600 and a free flight to their destination country.

Jennifer Arnold, a mother and community organizer, has parental authority for a work friend’s children should the parents get deported. Their arrangement says Arnold would care for them until the parents reemerge on the other end of the immigration court system, and she could fly the kids to where they are.

DOPAs have spread through immigrant circles in the past year, and not just among people who entered the country illegally, Arnold stressed.

“This includes people who have work permits because there’s no guarantee that you can’t be separated from your family,” she said. “Fear is in all places — people who have active (asylum) cases, who are on the way to a green card.”

Arnold also helps connect at-risk immigrants with trusted notaries. With her translating, the Minnesota Star Tribune interviewed a mother from Mexico who said she filled out DOPAs for two daughters — aged 10 and two — at an event at Colonial Market and Restaurant in south Minneapolis.

The Mexican mother said she has had a pending asylum claim for years.

Her greatest fear, the Mexican mother said, is that federal agents will detain her on the way to work or while grocery shopping, the only times she’s in public. Being deported to Mexico would upend her family’s lives, and she also fears being in indefinite detention without knowing whether her daughters are being taken care of.

“I want people to understand that we are being treated like we’re criminals, but our crime is that we’ve come here and we’ve been working,” the Mexican mother said.

She and her wife chose a longtime friend whom they’ve known for 10 years to assume responsibility for their kids because they don’t have any blood relatives in America with the ability to escort the girls out of the country.

Some metro schools with large populations of immigrant students have DOPAs on file.

Gabby Benavente, a bilingual associate educator who works with migrant kids at a Minneapolis public school, said conversations with her students’ parents have shifted over the past year. She said it’s gone from general anxiety to an urgent need to plan who’s choosing to stay, who’s self-deporting and who can be trusted to take custody of their children.

One student’s family faced that dilemma after the mother was detained, Benavente said. The kids wanted to stay in the United States, but the father was torn, fearful for his wife’s safety in their unstable country of origin, Ecuador. They came to her for help connecting someone who can help set up a change in custody.

“In my role, I’ve had to step up and kind of do things that feel more like the field of social work,” Benavente said.

DOPA lasts for 12 months but can be renewed indefinitely until the child turns 18, said Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid lawyer Pheng Thao.

If the parents are deported, the form can be mailed to the parents in a foreign country and sent back. The parent also can revoke custody at any point. Thao said in most of the situations he’s seen, parents are signing DOPAs to allow their children to stay in the U.S., where their futures are brighter, rather than hoping another adult can fly the children out of the country for reunification.

“It’s very difficult to put it into words, what’s going through the minds of these parents,” Thao said. “They have their own concerns and their worries about themselves. And at the same time, they have to prepare for what happens to their kids in the event they don’t come home from work.”

_____

©2026 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments