What is and isn’t new about US bishops’ criticism of Trump’s foreign policy

Published in News & Features

In recent weeks, Catholic leaders have been increasingly outspoken in their criticism of the Trump administration’s foreign policy, especially its military intervention in Venezuela and saber-rattling over Greenland.

On Jan. 19, 2026, the three cardinals heading U.S. archdioceses – Blase Cupich of Chicago, Robert McElroy of Washington, D.C., and Joseph Tobin of Newark – issued a rare joint statement. “The United States has entered into the most profound and searing debate about the moral foundation for America’s actions in the world since the end of the Cold War,” they began, calling for “a genuinely moral foreign policy.”

The cardinals quoted Pope Leo XIV’s annual address to the Vatican’s diplomatic corps, delivered earlier that month, in which he deplored that “a zeal for war is spreading,” and the norm governing the use of force “has been completely undermined.”

In follow-up interviews, Cupich criticized the U.S. operation to capture President Nicolás Maduro for sending a message that “might makes right.” Tobin noted that some members of the Trump administration seemed to be advancing “almost a Darwinian calculus that the powerful survive and the weak don’t deserve to.”

As a former foreign policy adviser to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and now director of Catholic peacebuilding studies at Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute, I know how rare it is that the cardinals’ short statement became headline news – especially because what they said mostly reiterated long-standing church teachings.

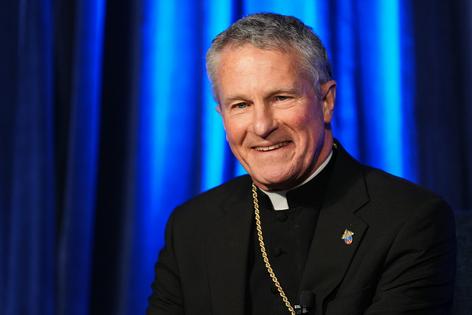

More novel, however, were statements by Archbishop Timothy Broglio, who leads the Archdiocese for the Military Services. In December 2025, Broglio issued a detailed critique of the morality and legality of the Trump administration’s strikes against boats in the Caribbean. In a January interview with the BBC, when asked if an invasion of Greenland could be considered just, he said, “I cannot see any circumstances that it would.”

It is unusual for an archbishop of the military services to question the morality of specific U.S. military interventions. After doing so, it is even more unusual to call on the nation’s leaders to respect the consciences of military personnel “by not asking them to engage in immoral actions,” and to remind service members that “it would be morally acceptable to disobey (such an) order.”

All of these statements continue U.S. bishops’ legacy of opposing virtually every major U.S. military intervention since Vietnam, except the invasion of Afghanistan.

That opposition reflects the Catholic Church’s centuries-old “just war” tradition and its increasingly restrictive approach to what counts as “just.”

Just war criteria limit when, why and how force may be used. According to the Catholic catechism, going to war is legitimate in cases where there are not other means of stopping “lasting, grave, and certain harm,” there is reasonable chance of success, and war will not produce “evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.”

In other words, war should be “a last resort in extreme situations, not a normal instrument of national policy,” as the cardinals noted in their statement. The Catholic Church presumes that war is a failure of politics.

That restrictive approach, which some conservative Catholics dub “functional pacifism,” has put church leaders in opposition to U.S. military interventions that reflect a much more permissive interpretation of just war. The permissive approach presumes that war might be a last resort, but it remains a form of politics – one tool in the foreign policy toolbox.

These contrasting approaches were especially evident in the nuclear debate of the early 1980s and the debate over the 2003 Iraq invasion.

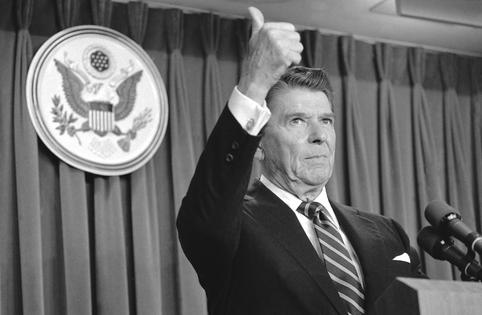

When Ronald Reagan first took office, his administration launched a massive nuclear buildup and deployed intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe, arguing that Americans were falling behind the Soviets in the Cold War.

In 1983, the U.S. bishops issued a highly influential letter, The Challenge of Peace, that opposed core elements of the administration’s nuclear policy. They called for a halt to the arms race, opposed the first use of nuclear weapons, and were skeptical of the morality of even a limited second, or retaliatory, use.

Their 103-page letter did not have a direct impact on U.S. nuclear policy, but it helped ensure that the just war tradition was no longer dismissed as outdated by policymakers and analysts. The pastoral was required reading in military academies.

One of the architects of Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. James Watkins, was troubled by the church’s criticism of deterrence, according to journalist John Newhouse. Watkins saw missile defense as a morally superior alternative, which is how the so-called “Star Wars” program was sold to a skeptical Congress and public.

Debate about overly permissive use of force reached its zenith in the lead-up to the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq in 2003. The administration argued that military force should not be restricted to defense against aggression. Preventive war was justified, in this view, to remove the potential danger Iraq posed in the aftermath of 9/11: a rogue regime, with weapons of mass destruction, and ties to global terrorists.

Pope John Paul II, U.S. bishops and Catholic leaders around the world vociferously objected, saying such a doctrine would emasculate the just war tradition and international law. As then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – who later became Pope Benedict – said in 2002, “The concept of ‘preventive war’ does not appear in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.”

As early as May 2002, U.S. bishops embarked on a series of meetings with White House officials, urging them not to go to war. In March 2003, John Paul sent the Italian Cardinal Pio Laghi to hand-deliver a letter to President George W. Bush urging the same.

It is not new for the church’s more idealist and cosmopolitan approach to international affairs to be in deep tension with a realist, “anti-globalist” U.S. foreign policy. In fact, the bishops have been more outspoken in the past than now.

But what is new, at least since the end of the Cold War, is church leaders’ growing concern about an intentionally norm-busting foreign policy. Past administrations offered legal and moral justifications for military inventions, such as the Bush administration’s claims that Iraq was a just war.

Trump, however, has abandoned any pretenses of his predecessors, telling The New York Times, “I don’t need international law.” The only limit on his international power, he said, is “my own morality.”

The bishops’ statements on his administration’s foreign policy are few and modest compared to the past. But with an American pope leading the way, they may prove the first salvo in more public and vigorous opposition by Catholic leaders.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Gerard F. Powers, University of Notre Dame

Read more:

Getting peace right: Why justice needs to be baked into ceasefire agreements – including Ukraine’s

2026 begins with an increasingly autocratic United States rising on the global stage

Even with Pope Leo XIV in place, US Catholics stand ‘at a crossroads’

Gerard F. Powers received a grant from the Nuclear Threat Initiative that helped support the Catholic Peacebuilding Network's Project on Revitalizing Catholic Engagement on Nuclear Disarmament. He is an expert consultant (unpaid) to the Holy See Mission to the UN. From 1987-2004, Powers was a senior advisor on international policy for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Comments